For a print-ready PDF of this page, click here.

What is risk pooling?

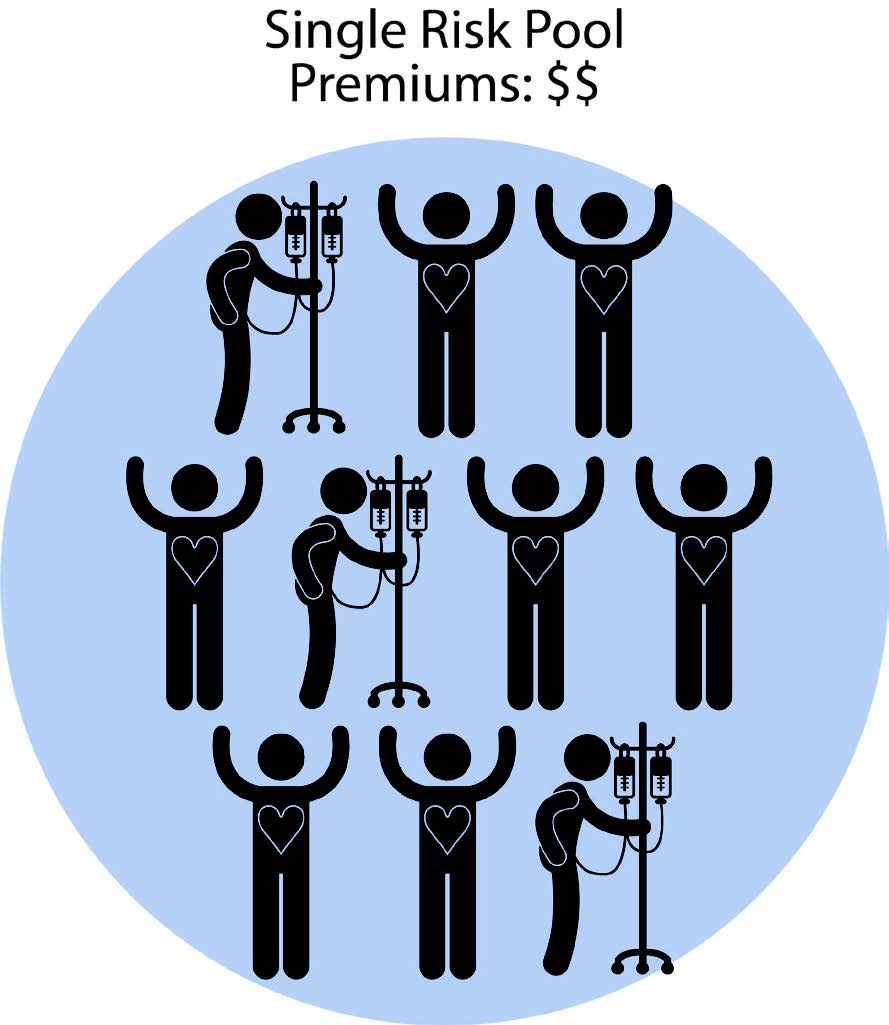

The pooling of risk is fundamental to the concept of insurance. A health insurance risk pool is a group of individuals whose medical costs are combined to calculate premiums. Pooling risks

together allows the higher costs of the less healthy to be offset by the relatively lower costs of the healthy, either in a plan overall or within a premium rating category. In general, the larger the risk pool, the more predictable and stable the premiums can be.

Is the size of a risk pool the only factor?

No. Although larger risk pools are typically more stable, a large risk pool does not necessarily mean lower premiums. The key factor is the average health care costs of the enrollees included in the pool. Just as a pool with healthy individuals can result in lower-than-average premiums, a large pool with a large share of unhealthy individuals can have higher-than-average premiums.

What is “adverse selection”?

“Adverse selection” describes a situation in which an insurer (or an insurance market as a whole) attracts a disproportionate share of unhealthy individuals. It occurs because individuals with greater health care needs, when given the opportunity, are more likely to purchase health

insurance and to purchase health insurance with richer benefits than individuals with fewer health care needs.

Why is adverse selection a problem?

Adverse selection increases premiums for everyone in a health insurance plan or market because it results in a pool of enrollees with higher-than-average health care costs. Adverse selection is a byproduct of a voluntary health insurance market in which people can choose whether and when to purchase insurance coverage, depending in part on how their anticipated health care needs compare with the insurance premium charged.

The higher premiums that result from adverse selection, in turn, may lead to more healthy individuals opting out of coverage, which would result in even higher premiums. This process typically is referred to as a “premium spiral.” Avoiding such spirals requires minimizing adverse selection and instead attracting a broad base of healthy individuals, over which the costs of sick individuals can be spread. Attracting younger adults and healthier people of all ages ultimately will help keep premiums more affordable and stable for all members in the risk pool.

Why do premiums depend on who buys coverage?

Health insurance premiums are set to pay projected claims to providers, as well as insurers’ administrative expenses, taxes, and profit. The largest component of health insurance premiums is the medical spending paid on behalf of enrollees. As a result, health insurance premiums reflect the expected health care costs of the risk pool. Because health spending is skewed—that is, a small share of consumers account for a large share of total health spending—if a risk pool attracts a disproportionate share of unhealthy individuals, premiums will be higher than they would be if the risk pool attracted an average population.

How does risk pooling currently work in the individual market?

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires that insurers use a single risk pool when developing premiums. The single risk pool incudes all ACA-compliant plans inside and outside of the marketplace/exchange within a state. In other words, insurers must pool all of their individual market enrollees together when setting the prices for their products. This means that the costs of the unhealthy enrollees are spread across all enrollees.

How does the ACA protect against adverse selection?

How does the ACA protect against adverse selection?

The ACA includes a number of provisions that are intended to broaden participation in the individual market. Among the more significant of these are the individual mandate, premium and cost-sharing subsidies for low-income individuals, and a limited open-enrollment period.

The ACA rules also support a level playing field. That is, the rules governing the insurance market regarding issue, rating, and benefit requirements apply equally to all insurers. In addition, the ACA includes a permanent risk adjustment program that transfers payments among insurers in the single risk pool based on the relative risk of their enrollees.

By limiting the adverse selection in the market as a whole and mitigating the effects of enrollee risk profile differences among insurers, the single risk pool requirement, uniform market rules, risk adjustment program, and provisions to encourage enrollment work together to facilitate market competition and the ACA’s pre-existing condition protections.

What if more flexibility were allowed in the ACA market rules?

If insurers were able to compete under different issue, rating, or benefit coverage requirements, it could be more difficult to spread risks in the single risk pool. Currently, risk adjustment is used to calibrate payments to insurers in the single risk pool based on the relative risks of their enrolled populations.

By reducing insurer incentives to avoid high-cost enrollees, risk adjustment helps support protections for those with pre-existing conditions. Some changes to market rules, such as increasing flexibility in cost-sharing requirements, could require only adjustments to the risk adjustment program. Other changes, such as loosening or eliminating the essential health benefit requirements, could greatly complicate the design and effectiveness of a risk adjustment program, potentially weakening the ability of the single risk pool to provide protections for those with pre- existing conditions.

What if some plans were allowed to avoid ACA rules altogether?

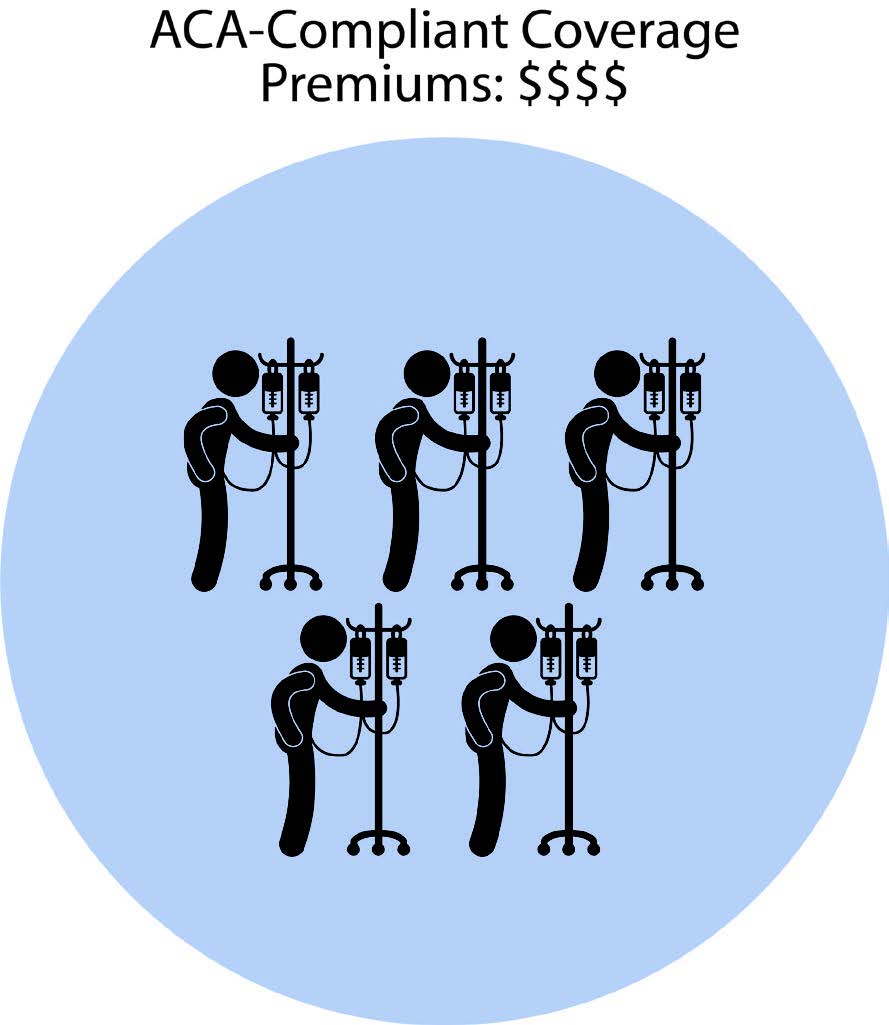

If some plans were allowed to avoid the ACA rules altogether, then plans competing to enroll the same participants wouldn’t be competing under the same rules. Noncompliant plans would likely be structured to be attractive to low-cost enrollees, through fewer required benefits, higher cost- sharing, and premiums that vary by health status.

Higher-cost individuals would tend to want the broader benefits and pre-existing condition protections of ACA-compliant coverage. Rather than having a single risk pool, in which costs are spread broadly, there would be in effect two risk pools—one for ACA-compliant coverage and one for noncompliant coverage. As a result, average premiums for ACA-compliant coverage could far exceed those of noncompliant coverage, thereby destabilizing the market for compliant coverage. The instability would be exacerbated if market rules facilitate movement of people between the two pools (e.g., if people with noncompliant coverage can easily move to compliant coverage when health care needs arise).

By transferring payments among insurers based on the relative risk of their enrollees, the ACA risk adjustment program can reduce premium differences resulting from some insurers attracting more costly enrollees than others. However, risk adjustment programs transfer payments within the same risk pool, but not between pools, especially when the different pools have different issue and rating rules. Therefore, in a market with separate risk pools for compliant and noncompliant coverage, costs would no longer be spread over the broad enrollee population. In addition, for risk adjustment to work properly, the benefit coverage requirements need to be fairly similar across plans. Even if the compliant and noncompliant plans were pooled together for risk adjustment purposes, the potentially large differences in underlying benefits between compliant and noncompliant coverage would make risk adjustment extremely difficult to implement. And any resulting risk transfers from noncompliant plans to compliant plans would be very high, thus negating much of the premium advantages of noncompliant coverage.

Instead of using risk adjustment to mitigate the higher premiums needed for compliant coverage, external funding could directed to the compliant pool, for instance in the form of a reinsurance program. However, the funding for such a program would have to be substantial and permanent.