By Tim Geddes

As a kid growing up in Michigan, I had the opportunity to play a lot of hockey. Maybe it is my imagination, but the winters seemed colder back then-cold enough that my friends and I could skate on frozen ponds for nearly the whole season. As I got older, I convinced my parents to allow me to join an organized league and play in indoor rinks. Over the years-through hundreds of hours of ice time and a lot of thinking about the game-I developed a reasonable proficiency in skating, passing, shooting, and even some of the rougher elements of the sport. Eventually, life’s priorities pushed hockey largely out of my life. There was college, actuarial exams, family, and work. Playing in the midnight beer league sounded fun, but the 7 a.m. business flights the next morning made it impractical.

Decades passed without me skating regularly, and I gradually lost interest in watching NHL games on television (which correlated with the Red Wings deep slide into irrelevance). But recently, I had the chance to watch one of the Stanley Cup games while I was stuck at the airport because of a delayed flight. After I got past my initial shock that a team from Florida was playing (and winning) the finals, I was drawn into the game and started to notice things had changed. Certain rules had been modified-around what goaltenders could do, what constituted icing, how long passes could be, and where face-offs occurred. New penalties seemed to have been introduced, with unfamiliar hand gestures from the referee. The tools the players used were different than I remembered as well-skates had removable blades, sticks were made of high-tech materials, and helmets looked much more robust. In short, the game had evolved while I had not been paying attention.

A contributing factor to my abandonment of hockey was the need to study for actuarial exams. The hundreds of hours spent in ice rinks shifted to hundreds (if not thousands) of hours spent in front of a book, computer, notepad, and calculator. It was through those exams, as well as on-the-job experience, that I built proficiency in my professional craft.

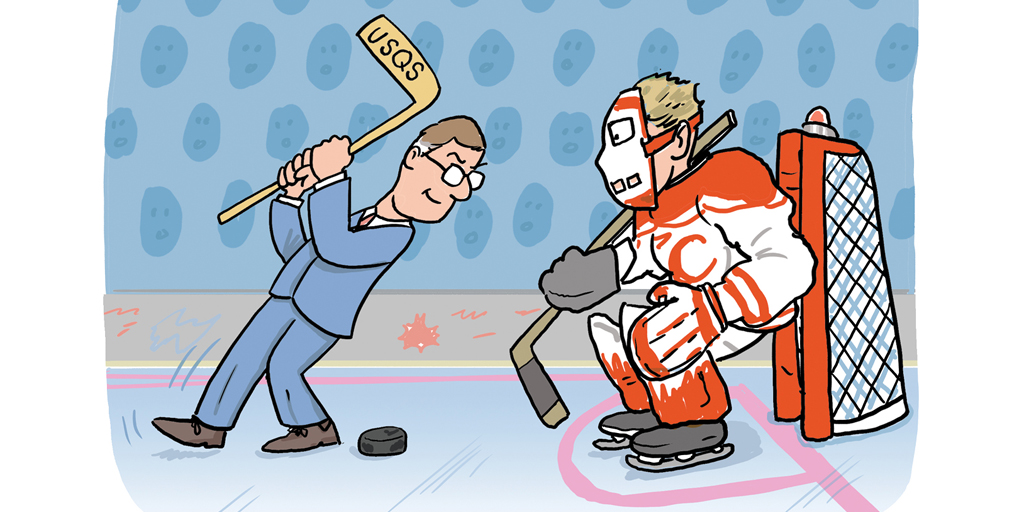

USQS Requirements

Precept 2 requires that an actuary perform actuarial services only when he or she “…satisfies the applicable qualification standards.” The U.S. Qualification Standards (USQS)-as promulgated by the Academy’s Committee on Qualifications-contain section 2, which provides a General Qualification Standard applicable to any actuary who is issuing a Statement of Actuarial Opinion (SAO) while providing actuarial services. The USQS recognize the importance of the education and examination process in requiring actuaries to satisfy a basic education requirement prior to issuing any SAOs:

Section 2.1(a) Basic Education: Have achieved 1) through education or mutual recognition, a Fellow or Associate designation from either the Society of Actuaries (SOA) or the Casualty Actuarial Society (CAS), 2) the Enrolled Actuary (as defined in section 2.1.1) designation, or for all others 3) membership in the American Academy of Actuaries through its approval process.

The USQS continue in section 2.1(b) by outlining a demand for three years of responsible actuarial experience. The requirement to have both foundational academic knowledge of the subject and practical working experience acknowledges the criticality of making black-and-white technical decisions as well as gray professional judgment choices.

Section 2.1(c) expands on the previously mentioned general requirements, demanding that an actuary be knowledgeable of the U.S. laws applicable to the specific SAO. A requirement of familiarity with U.S. actuarial practices and principles is also included. Section 2.1(d) adds additional qualification standards which relate to the area of actuarial practice or any particular subject within the area of actuarial practice. Those supplementary strictures enforce some combination of another basic education obligation within the area of practice (either achieved through the pursuit of credentialing or via additional educational opportunities) and an apprenticeship-like requirement of working under another actuary qualified to issue the SAO for a minimum time period (which can vary from one to three years depending on the level of credential achieved and education pursued).

Importantly, section 2.1.2 clarifies that the basic education requirement for an area of actuarial practice or a particular subject area within an area of actuarial practice need only be met once. The acceptance of long-ago education prevents actuaries from the constant challenge of intense studying and examination. However, without further rules, an actuary’s required skills could be frozen in time upon credentialing.

Addressing this critical need for maintenance and continuous enhancement of skills, the USQS devote section 2.2 to continuing education (CE). Section 2.2.1 provides an excellent rationale for the CE requirement by emphasizing,

“Actuarial practice is grounded in the knowledge and application of actuarial science, a constantly evolving discipline. If actuaries are to provide their principals with high-quality service, it is important that they remain current on emerging advancements in actuarial practice and science that are relevant to the actuarial services they provide.”

The USQS rest on that rationale to clarify that all actuaries seeking to satisfy the General Qualification Standard must complete and document at least 30 hours of relevant continuing education every year. Because of our commitment to professionalism, three hours of that total must be related to professionalism, and one hour must cover bias topics.

Meeting the CE Standard

Relevant CE is clarified to mean that it (a) broadens or deepens an actuary’s understanding, (b) exposes the actuary to new and evolving techniques, (c) expands an actuary’s knowledge of practice in related disciplines, and (d) facilitates an actuary’s entry into a new area of practice.

It is important that, while 30 hours overall must be achieved and documented annually, only six of those are required to be from organized activities, defined as those which involve interaction with actuaries or other professionals working for different organizations. Some examples of organized activities include conferences, webcasts, in-person or online courses, and relevant committee work. Possible CE, which is relevant but not considered organized, might be reading actuarial literature, reviewing statutes, writing papers, or viewing replays of webcasts.

Also, please note that the USQS CE requirements apply to all actuaries subject to the Code of Professional Conduct when issuing statements of actuarial opinion. Those actuaries under the jurisdiction of the Joint Board for the Enrollment of Actuaries’ (JBEA) CE requirements, who are also members of one of the other actuarial organizations that have adopted the Code, must consider compliance with both sets of continuing education on an ongoing basis. Notably, while the JBEA rules operate on a three-year cycle, actuaries covered by the USQS rules must continue to satisfy USQS requirements annually if issuing SAOs.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Actuarial Board for Counseling and Discipline (ABCD) inquiries often involve a failure to obtain or document sufficient CE credits. CE forms a vital part of our ability to uphold the reputation of the actuarial profession. As the rules and tools of our professional trade evolve, be sure to keep your eyes on the professionalism puck!

TIM GEDDES is a member of the Actuarial Board for Counseling and Discipline. He was the Academy’s vice president, professionalism, from late 2022 to late 2024. He previously served as vice president, retirement, and as a member-selected director on the Academy Board. In his youth, only the really tough survived the winters and the hockey.