| Issue Brief |

Regulatory Options for Long-Term Care Insurance Innovation |

|

MARCH 2021 |

|

Download a PDF version here. IntroductionIn recent years, the low level of penetration into the potential market by private long-term care insurance (LTCI), and increasing growth in state Medicaid budgets due in part to the long-term care (LTC) needs of a growing elderly population have prompted a number of proposals for reforms in the way LTC is financed in the United States. In 2017, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ (NAIC) Long-Term Care (LTC) Innovations (B) Subgroup published a list of Federal Policy Options to Present to Congress1 that included possible changes to support the LTCI market in positive ways and strengthen the overall framework of financing of LTC. Some of these options would need to be addressed through changes in laws or regulations at the state level, the federal level, or both. This issue brief examines some of those options which are specific to regulatory changes and discusses recommended changes and actuarial implications regarding those ideas. Option 3: Remove the HIPAA2 requirement to offer 5% compound inflation with LTCI policies and remove the requirement that DRA3 Partnership policies include inflation protection and allow the States to determine the percentage of inflation protection. |

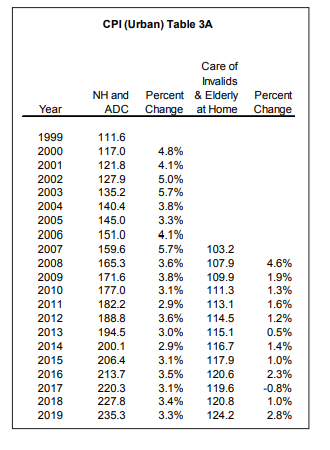

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requires that companies offer an automatic 5% compound increase to the daily or monthly maximum when writing LTCI. This is consistent with the requirement included in the NAIC Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act (#640) that was first promulgated in 1986 and adopted in many states by 1993. Insurers may also offer other inflation protection options. Today, the required offer amount of 5% inflation protection seems arbitrary, yet it was considered reasonable when the requirement was first established. The following table of the Nursing Home (NH) and Adult Day Care (ADC) component of the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) gives the data required to understand why. The addition of the separate home health care component in 2007 emphasizes the change.

|

Current HIPAA and state regulations do not prohibit LTCI companies from offering other inflation options, including lower increases in the maximums, limited time periods for the increases, or benefit increases that are level amounts in all years (i.e., simple inflation rather than compound); they only require that LTCI companies offer the 5% compound inflation protection as an option among other options offered by the company. As can be seen by the table above, recent trend has been less than the 5% level. Furthermore, the regulations do not require that the policyholder purchase a daily maximum benefit that is reasonable for the benefits at the time of purchase. The policyholder may purchase an amount that is relatively low or relatively high. From this point forward, the discussion in this issue brief assumes that the policyholder started with a reasonable daily maximum as such an assumption simplifies the concepts being made. |

|

Typically, Medicaid requires individuals to spend down certain assets so that they are presumed to require assistance in the form of Medicaid. The Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) included a “Partnership” LTCI program that exempts some of a policyholder’s assets from being counted toward qualifying for Medicaid. Some assets, such as the equity in a primary residence, are exempt from being spent down, and when a Partnership LTCI policy pays benefits, assets representing the amount of those LTCI benefits are exempt when applying for Medicaid.

State requirements for LTCI vary as to the details, yet riders to insurance policies to provide increases in benefits to address inflation are usually required at certain ages. For example, the purchaser may be required to have a compound automatic increasing benefit if they are under age 62. If between the ages of 62 and 75, they may be required to have a cost of living rider, and if purchasing at an age over 75, no rider may be required.

In order to satisfy HIPAA and state regulations, an LTCI Partnership policy applicant must be offered an automatic 5% compound increasing maximum. A Partnership policyholder may find value in such an offer despite today’s low inflation environment for at least two reasons. First, inflation may increase over the course of the coming decades before the policyholder actually requires benefits. Second, once they do qualify for benefits in a situation where the benefits otherwise did not keep up with inflation, they may spend down their assets to pay for the needed services before using up all of the benefits in the policy.

An insurer may have a different perspective. Being required to offer the 5% compound inflation protection can contribute to limited insurer participation in the market. In the context of today’s relatively low inflation environment, the requirement to offer a 5% compound inflation protection for the lifetime of the product could invite adverse selection. Insurers charge smaller premiums for lower levels of benefits. When lower benefit options seem sufficient, those who see themselves as requiring care may have a greater incentive to pay more to purchase the higher benefit option.

The NAIC proposal provides the following additional comments:

Removal of the requirement that insurers offer 5% compound inflation protection with LTCI policies and the requirement that Partnership policies include inflation protection would increase insurer flexibility when designing products and could lead to lower premium costs. At the same time, consideration should be given to requiring an offering of some type of inflation protection to ensure consumers continue to have the option to protect themselves against increasing LTC costs. [Note: this would require both federal regulation and NAIC model changes, and states would need to adopt the revised NAIC model changes.]

Another approach to addressing the issue of appropriate coverage would be to identify initial daily/monthly coverage amounts in the requirements instead of requiring inflation coverage in the benefit design.

A 5% compound inflation increase is also considered by some LTC insurers and potential insurers as creating an excessive amount of accumulated benefit coverage in later years when most of the LTCI claim is expected to occur. A 2013 study published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services determined that 20% of LTCI companies that have exited the marketplace (i.e., ceased sales of new LTCI policies) might reconsider entering the market if the 5% mandatory compound inflation benefit were reduced to a 2% mandatory offering.4

If the 5% mandatory compound inflation offering is not repealed/modified by the federal government, another potential innovative solution would be for LTCI companies to index the annual inflation benefit to account for the annual increase in the cost of applicable LTC services. To be considered feasible, this could include an annual or cumulative cap on the inflation amount (insurers often require a cap to their risk exposure.) Under this approach, there is less risk of over-insurance, but this risk reduction would be exchanged for pricing risk. Pricing is less certain when benefit levels are less certain. If expected inflation is less than 5%, premiums could be less expensive (as compared with policies with the mandatory 5% compound inflation offering), which, in turn, would make standalone LTCI policies more affordable for consumers interested in purchasing LTCI. If this alternative option were allowed in place of the mandatory 5% compound offering, it would likely be more popular and might encourage more market participants.

Required inflation protection also creates challenges for some combination products. Mixing benefits from various products with LTC benefits becomes complicated when the LTC portion is required to have an inflation option that may not be reasonable or rational for the other benefits in the package. If the requirements to offer inflation benefits is maintained for traditional standalone LTCI products, it would be beneficial to innovation if a clearly articulated exception were made for combination products.

While designed to protect consumers (as well as the Medicaid program), the required inflation protection has the impact of making the partnership program policies prohibitively expensive for many individuals.

Option 5: Allow products that combine LTC coverage with various insurance products (including products that “morph” into LTCI). Many stakeholders emphasized the need for regulatory changes at the federal level to allow for LTCI innovation and market expansion. One consistent view of stakeholders is the need to expand products that can address a consumer’s needs over time. Products that offer life, disability, critical illness, supplemental, and other benefits could be allowed in various combinations with or for conversion to LTCI, such as after the policyholder reaches a certain age. Legislative changes specifically allowing this type of product would be required for pertinent federal tax and NAIC governing documents.

Long-term care combination products (also referred to as “LTC combo products” or “LTC hybrid products”) provide a potentially attractive alternative to traditional standalone LTC coverage. Product designs can vary considerably. In general, LTC combo products include any insurance policy that combines life and/or annuity coverage with LTC coverage over the life of the policy. LTC combo products can be built on either a life insurance chassis or an annuity chassis, with LTC coverage provided either in the form of a rider or as additional coverage integrated directly into the base life/annuity product. LTC combo products may provide a benefit that is completely distinct from the life insurance or annuity benefit; alternatively, the LTC coverage may be payable in the form of extended benefits upon the exhaustion of underlying death or annuity benefits. In some cases, LTC combo products include a conversion feature in which, for instance, life insurance coverage may be provided for a number of years (e.g., to age 65) followed by LTC coverage following a defined age or policy duration.

Given the hybrid nature of LTC combo products, these policies present several issues that warrant guidance or regulation at the federal level, either through federal government policy or at the state level, including through the NAIC. The remainder of this section discusses these issues. Specifically,

- Issues related to federal taxation;

- The need for clarity regarding the application of statutory valuation standards to LTC combo products; and

- The uncertainty concerning the governing requirements related to product design.

Federal Taxation

The hybrid nature of LTC combo products raises several important issues with respect to federal taxation. For both standalone life insurance/annuity products and standalone LTC products, federal laws set forth the requirements for policies to be considered “tax qualified,” meaning that benefit payments are not taxable at the policyholder level. For life insurance policies, Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 7702 provides such standards; for LTC, HIPAA defines the federal tax qualification standards. Being neither uniquely a life product nor an LTC product, it is not always possible to classify (and test) an LTC combo product under existing tax qualification standards.

Insurers and policyholders could benefit from federal guidance regarding tax qualification of broad classes of LTC combo products. Specifically, such guidance that would clearly articulate:

- Safe harbor product designs that would be considered “tax-qualified,” allowing for federal income tax-free payment of benefits to policyholders;

- For products that do not meet such safe harbor designs, the process required to obtain an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) ruling regarding tax qualification; and

- Any actuarial testing (analogous to guidance pursuant to IRC Section 7702) required to demonstrate compliance with federal tax qualification.

LTC combo products also raise unique challenges concerning the preparation of insurance company federal income tax filings. Recent tax reforms (i.e., the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017) materially changed federal tax law applicable to life and health insurance companies, including specifically the basis for reporting tax reserves and insurance company taxation.

Federally prescribed limitations on tax reserves may not always have a clear interpretation for LTC combo products. Effective in January 2018, federal tax law requires that life and health insurance companies begin phasing in (over eight years) a cap on the reported tax reserve for any obligation that involves life or morbidity contingencies. After the eight- year phase-in, the cap limits reported tax reserves to the greater of 92.81% of reported statutory reserves and the cash surrender value of the policy. For LTC combo products that feature an account value-based life or annuity product, the application of the 92.81% cap is not always clear. For instance, if the product functions as an annuity product, the account value or cash surrender value may be deductible for federal income tax purposes; if alternatively it functions as an LTC disabled life reserve, the 92.81% cap may apply.

Proxy deferred acquisition cost (DAC) rules vary between life/LTC products and annuity products, in particular with respect to the capitalization rate. Certain LTC combo products do not fit neatly into existing proxy DAC capitalization rules.

To address this, the rules would also need to be modified to provide insurers such guidance on tax filing issues related to combo products.

Statutory Valuation Requirements

Because LTC combo products are neither pure life/annuity products nor pure LTC products, there is uncertainty concerning the applicable statutory valuation requirements for LTC combo products. For instance, should a Universal Life policy with an LTC rider that offers extension of benefits be reserved under applicable Universal Life requirements, the LTC requirements, or some combination of Universal Life and LTC requirements with consistent or inconsistent valuation assumptions?

Actuaries must consider valuation requirements when developing and pricing products. Uncertainty with respect to future reserve requirements may: 1) provide a disincentive for insurers to develop innovative products; 2) result in the development of “overpriced” products, because of an overly cautious or conservative view with respect to uncertain valuation requirements, or 3) result in taking an aggressive pricing and valuation approach that may lead to financial challenges or even insolvency in the future. Such conditions may result in an unmet market need, products that are unattractively priced or underpriced products.

It would be preferable if valuation requirements were principle-based (meaning they reflect the substance of the policy and the expected cash flows under such policy) rather than retrofitting LTC combo products into previously existing valuation requirements that were designed for other purposes. A principle-based framework would allow flexibility to accommodate future innovations in product design and ensure holistic reserve adequacy.

Governing Standards Related to Product Design

Current governing standards address standalone LTC coverage, life insurance coverage, and certain LTC combo products including accelerated benefits and extension of benefits; however, unique product designs are discouraged if they do not fit into one of these categories. An example of this is a product designed by Minnesota to develop affordable LTC insurance options targeted at middle-income consumers. The product design combines term life insurance until age 65 and then LTC coverage after this age. Consumer research, both at the state level and the national level, indicate a strong demand for such a product. The following is an excerpt from the “LifeStage Protection Product Final Report”5 prepared for Minnesota Department of Human Services Own Your Future Initiative by O’Leary Marketing Associates LLC.

Minnesota’s Own Your Future initiative received funding to conduct qualitative consumer research on two products, one of which was LifeStage. In addition, LifeStage was chosen as one of two products that were part of a major nationwide research project conducted by the Society of Actuaries (SOA) Long-term Care Think Tank. Results from both research projects indicated strong interest in the LifeStage concept among target consumers. In Minnesota, approximately 90% of 37 focus group participants rated the LifeStage product concept as either an A or B. In the SOA research 49 percent of respondents indicated an intent to purchase LifeStage and that translated to a two-year trial rate of 21 percent.

However, carriers appear hesitant to pursue such a product, noting uncertain regulatory constraints as being part of the reason not to pursue.

This type of product does not have to be limited to life insurance, and other product combinations including disability, critical illness, supplemental, and other benefits could also be combined with or used for a conversion to LTCI. Legislative changes specifically allowing this type of product would be required for federal tax provisions and NAIC model and/or guidance changes. Absent these changes, any attempted product designs would typically be modified to fit within current regulations such as using non-tax qualified products. Another area of ambiguity is whether LTC premiums/charges within a combo policy could be subject to the level premium beyond attained age 65 requirement of the NAIC LTC model regulations. Allowing LTC increasing premium schedules within combo products can foster the development of designs where the cost of insurance for the LTC rider is similar to Universal Life allowing more flexibility with the payment of premiums.

The capital requirements and targets for these products are unclear. For example, currently the NAIC Risk-Based Capital (RBC) formula does not recognize the various additional LTC risks included in combo products and only addresses the risks of the base coverage. It is possible that the NAIC or rating agencies could modify their formulas even retroactively to address this concern should these products become more prevalent. This creates risk for the carrier that the capital requirements could change after the business is issued. The possibility for such changes creates uncertainty that could inhibit market participation for innovative combination products.

Option 6: Support innovation by improving alignment between federal law and NAIC models (HIPAA and DRA). HIPAA and the DRA require that LTC policies comply with specific provisions of outdated versions of the NAIC model act and regulation. The NAIC regularly updates its models, and this may can result in confusion as the NAIC models evolve while federal law continues to reference old models. Therefore, it may make sense for federal law to reference and require compliance with pertinent provisions of the “current” version of the NAIC models for newly issued contracts (with appropriate transition rules to address model amendments) rather than require compliance with specific provisions of a specific version of the model. This would allow federal law to evolve as the NAIC, a collaborative body with active involvement of consumer and industry representatives, updates the models as needed. This would increase the flexibility of federal law to adapt to the evolving LTC market and regulatory requirements, and reduce confusion and possible inconsistencies between state and federal law.

This option directs the issue to one particular difficulty between two federal regulations and the NAIC model LTC regulation. Both the HIPAA and DRA reference a particular, dated version of the NAIC model regulation. The NAIC suggests the federal regulations could refine the NAIC references to automatically move with changes to the NAIC model regulation. Alternatively, HIPAA and DRA could be modified to define LTC independently of the NAIC model regulation.

Beyond what is identified by the NAIC in this option, other misalignments with federal law also appear to stifle demand and therefore innovation. Some believe that the availability of Medicaid in and of itself discourages people from purchasing private solutions to LTC needs. This supposition seems in line with the commonly accepted concern that individuals do not think of themselves as ever needing LTC services, and therefore do not plan for it. Instead, they spend down their assets and qualify for Medicaid. Material exemptions to the spent down requirements also reduce demand. Therefore, traditional insurance as well as innovation may be affected by the presence of Medicaid.

Furthermore, the federal income tax treatment of innovative programs that are non-tax- qualified may discourage any movement away from the specific structure required by the NAIC LTC model regulation. Reserves for products that do not qualify as LTCI, use a two-year preliminary term basis, increasing taxable profits in the early years of the policy. This compares to a one-year preliminary term basis for LTCI tax reserves.

For another example of federal state regulatory misalignment, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services appears to rely upon the NAIC model LTCI regulation to identify what policies are exempt from a requirement in the federal Genetic Information and Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). LTCI insurers are permitted to ask family history questions when an individual applies for coverage, but in general GINA does not allow health insurers to ask for family history or genetic information. If a product design must be filed as a limited benefit health plan because it does not satisfy the NAIC model LTCI regulation, the product may not be exempt from the GINA requirement the way LTCI is. Yet without the ability to ask family history in underwriting the applications, the innovation may not be viable.

Option 9: Explore adding a home care benefit to Medicare or Medicare Supplement and/or Medicare Advantage plans. Medicare provides extensive acute care coverage but more limited post-acute coverage (home health and skilled nursing facility care). Medicare Advantage and gap Medigap plans fill the gaps in Medicare. But most LTC services are not covered by Medicare, leaving a considerable gap in coverage for post-acute care. The most comprehensive Medicare Advantage and gap Medigap plans do not cover LTC services, other than the daily Medicare co-payment for the 21st to 100th day of Medicare covered skilled care; they do not cover intermediate care, assisted living, Alzheimer’s, custodial or adult day care. Medigap and Medicare Advantage plans only supplement Medicare covered nursing home care on a temporary basis and help with hospice coverage. There has been discussion of adding either something akin to a long-term care benefit or, less extensive, new home and community-based benefits either to Medicare (which would affect supplemental carriers) or to Medicare Advantage and/or Medigap plans. If new benefits were provided in supplemental coverage it could make those products more expensive, though that increased cost might be offset by savings from delaying or preventing the use of more expensive institutional care. [Note: this would require federal changes to Medicare, changes to the NAIC models governing Medigap benefits, and adoption of revised NAIC models by states.]

There are significant issues with the concept of adding coverage for LTC services through Medicare-related programs, including Medicare, Medicare Supplement (a.k.a. Medigap) plans, and Medicare Advantage. Three of these issues will be discussed here. They are adverse selection, portability, and prefunding. These issues are somewhat interrelated and individually are problematic, but in combination they present a significant challenge to this option for it to be viable.

Adverse Selection

Adverse selection occurs in any type of optional insurance coverage when large benefits are available and individuals who have the decision to obtain the coverage have a reasonable ability to anticipate a significantly higher than average need for the coverage in the immediate future. LTC coverage is highly susceptible to adverse selection. For most LTC coverage enrollment, there are substantial underwriting requirements to protect against some adverse selection.

Extensive underwriting is not typical for Medicare-related programs. In fact, there is little or no underwriting in many situations. If coverage for LTC services are added as an option to Medicare, Medicare Supplement, or Medicare Advantage plans, the need for appropriate levels of underwriting beyond the levels typical for these programs would need to be considered.

Prefunding

Most LTC coverage programs rely on significant prefunding. Premiums are accumulated for long periods of time—years or even decades—prior to the prevalent need for the covered services. Medicare-related programs rely heavily on funding from taxes and pay-as-you-go funding for current services. Integrating funding needs for extensive LTC benefits, particularly if they are optional coverages, would be difficult.

As an example, Medicare Advantage plans and Medicare Supplement plans provide benefits established and funded on an annual basis, so long-term funding needs would be difficult to incorporate, especially on an optional basis.

Minor benefits could be added to one or more of the programs as an initial step, but significant changes in laws and regulations would be needed if these are to be included as a permanent part of the program. And if the benefits are minor, they may not provide enough coverage to resolve the significant financial burden that the cost of LTC services represent.

Another approach would be to include LTC benefits as a mandatory coverage in all Medicare Supplement and Medicare Advantage plans. However, this would increase the cost for all consumers and could lead to lower levels of medical coverage as individuals consider their own financial decisions.

A related concern that is often expressed with LTC coverages is the stability of premiums. However, premiums for Medicare Supplement coverages often increase every year. It is unclear how it would be perceived if LTC coverage was included in one or more of those plans.

Portability

It is important that LTC benefits are maintained over longer periods of time to ensure that the coverage is available when the services are required. Medicare benefits themselves are portable, but it is unclear how portability of LTC benefits would be applied to Medicare Supplement and Medicare Advantage plans. While long-term stability of Medicare-related coverage may be desirable, consumer choice and flexibility over time is also beneficial to many. Designing a plan that contains flexibility and portability of coverage would need to be considered.

In summary, adding LTC coverage to Medicare related programs in a financially viable manner would be challenging. Such an addition would need to be well designed, addressing funding, optionality, and portability. Significant changes in laws and regulations would need to be made both at the state and federal level.

Overall Conclusion

The NAIC has identified several options for improving the environment for financing of LTC services. Several of these would require significant legislative and regulatory changes, both at the state and federal levels, while also needing further consideration over design issues that would support their financial viability. Continued discussion and evaluation of various concepts are encouraged so that sound solutions can be identified and pursued.

|

[1] National Association of Insurance Commissioners, “Long-Term Care Innovation (B) Subgroup: Federal Policy Options to Present to Congress,” 2017. [2] Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. [3] Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 [4] Exiting the Market: Understanding the Factors Behind Carriers’ Decision to Leave the Long-Term Care Insurance Market; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, July 1, 2013 (page 47, table 12). [5] O’Leary Marketing Associates LLC, “LifeStage Protection Product Final Report,” p.5, December 2018. Prepared for the Minnesota Department of Human Services Own Your Future Initiative. |

Craig Hanna, Director of Public Policy Members of the Long-Term Care Reform Subcommittee, which authored this issue brief, include Mark Billingsley, MAAA, FSA; Dave Bond, MAAA, FCA, FSA; Seong-min Eom, MAAA, FSA; Clark Heitkamp, MAAA, FSA; Bruce Stahl, MAAA, ASA; Bob Yee, MAAA, FSA; and Adam Zimmerman, MAAA, ASA. |