| Issue Brief |

An Actuarial Perspective on the 2020 Social Security Trustees Report |

|

MAY 2020 |

Download a PDF version here.

The Social Security Trustees Report is a detailed annual assessment of the solvency of the Social Security program. It also can inform discussions of Social Security’s financial problems and possible solutions. The Social Security Administration’s actuarial staff prepares and certifies the financial projections for the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program, under the direction of the Social Security Board of Trustees. The report does not reflect the recent impact of COVID-19, which is expected to result in lower tax income to Social Security. The report’s actuarial opinion states that “assessment of the implications [of the pandemic] will take time and will be provided by the time of the next annual report.”

|

The 2020 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Federal Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Funds had the following highlights:

The sooner a solution is implemented to ensure the sustainable solvency of Social Security, the less disruptive the required solution will need to be. † Assumes that the OASI and DI tax rates can be reallocated between trusts (which Congress has allowed in the past). |

Social Security Out of Balance—Sooner than Originally Projected

The last substantive changes made to the Social Security system occurred in 1983. At that time, the trustees projected that all scheduled benefits would be payable through 2057, the end of the 75-year projection period. That projection was based upon demographic assumptions regarding longevity, birth rates (fertility), immigration, and disability incidence as well as economic assumptions regarding interest rates, wage growth, inflation, and productivity gains. The trustees anticipated the increased longevity of the baby boom generation and the drop in fertility in subsequent generations. Their 1983 population forecasts have stood the test of time. The economic experience of the country, however, has varied considerably from what anyone in 1983 could have anticipated.

In order to support the future benefits detailed in the 1983 amendment, including the ability to pay the baby boom generation in retirement, more money was accumulated in the OASDI trust funds than was required to pay immediate benefits. At the end of 2019, the amount in the trust funds was $2.9 trillion. As we have known for many years, this amount in concert with taxes and trust fund earnings will likely not support benefits through 2057. The trustees project that full benefits will only be sustainable until 2035— the date the trust fund is expected to be depleted. Benefits will continue to be payable after that date but not fully unless legislative action is taken.

The projected date at which the system will no longer be able to pay full benefits is based on an analysis of projected income and benefits under deterministic assumption sets as well as on stochastic projections of the future. The deterministic assumption sets are referenced as intermediate, low-cost, and high-cost. The intermediate assumptions reflect the trustees’ best estimates of future experience. The trustees also present low-cost and high-cost results to provide a range of possible future experiences. They note that actual future costs are unlikely to be as extreme as those portrayed by the low-cost or high-cost projections.

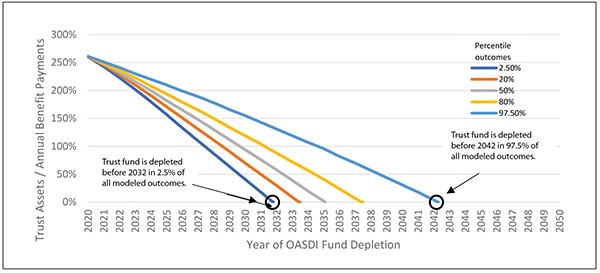

Table 1 shows when the trustees project the system will no longer be able to pay full OASDI benefits under the intermediate assumption set as well as stochastic projections.

Table 1: Projected Year in Which Current System Cannot Pay Full OASDI Benefits

| Figure II.D7 from Trustees Report, Stochastic Model of OASDI Trust Depletion |

|

The 95% confidence interval referenced in Table 1 is shown in this graph by the leftmost and rightmost lines. In 95% of the scenarios generated by the trustees’ stochastic model, the OASDI trust fund is depleted sometime between 2031 and 2042. This type of analysis shows the inherent uncertainty in projecting a complex system like OASDI and also shows the imbalances in the system are unlikely to be corrected without legislative action.

Demographic Issues

The projected imbalance in the system is essentially a story of demographics and wages. We first look at demographic issues. Wage and other economic issues are discussed later in this brief.

The series of pie charts below show the current and forecasted ratio between working-age adults and non-working-age adults in the United States. In rough terms, the population in the 20-64 age group comprise the workers paying taxes into the Social Security system to provide benefits generally to those in the age 65+ group. The projected system imbalance is a result of the taxpayer group becoming a smaller percentage of the overall population and thus not providing enough income to the system to pay all projected benefits to a relatively larger beneficiary group.

| U.S. Population: Comparison of Working Age Adults to Adults Age 65+ |

|

The projected aging of the U.S. population has been long anticipated. The “baby boom” from 1946 to 1964 was followed by a drop in the fertility rate and a materially smaller generation of succeeding workers (see Chart 1). In addition, average life expectancy at age 65 has increased significantly and is anticipated to continue increasing (see Chart 2). These two demographic trends combine to put stress on the Social Security system.

|

Chart 1

|

Chart 2

|

| Source: 2020 Trustees Report, Table V.A1 and Table V.A4, Single Year Tables | |

One way to express the impact of lower fertility rates, increased longevity of Social Security beneficiaries, and the overall aging of the US population is to measure the ratio of projected workers to beneficiaries. Chart 3 shows the number of workers per beneficiary starting in 1980 and projected forward.

Chart 3: Projected Workers per Beneficiary

|

The decline in workers per beneficiary has been anticipated for several decades. The red points in Chart 3 show the projection from the 1983 Trustees Report.

Immigration is a third demographic trend that affects the finances of Social Security, although in a modest manner. According to the Trustees Report, the OASDI cost rate decreases slightly with higher net immigration because immigrants largely comprise young age groups, thereby increasing the numbers of covered workers earlier than the numbers of beneficiaries. Appendix D, Table VI.D3 of the Trustees Report, and Table 2 below, show that increasing immigration by 337,000 people per year (from the intermediate assumption of 1,261,000 per year to the low-cost assumption of 1,598,000 per year) decreases the actuarial deficit by 0.25% of payroll yet leaves the projected trust fund reserve depletion date unchanged at 2035.

Cost Rates

Today’s Social Security tax rate (6.2% of earnings up to the wage base for both employees and employers) has been in place since 1990. During the period when the ratio of workers per beneficiary was higher than it is now, this rate allowed the system to build a $2.9 trillion reserve. However, the tax rate is not sufficient to support projected benefits beyond the middle of next decade. As the number of workers per beneficiary decreases, the taxes paid by those workers along with other system income cannot keep pace with the projected increase in benefit payments. Without any amendment, the cost of paying full benefits is projected to exceed income as soon as soon as 2021. Once the reserves are depleted, incoming tax revenue will only be able to support 79% of the projected benefits.

|

The trustees define the annual cost rate of the system to be the projected cost of benefits divided by the projected taxable payroll. Looking at the likely path of the future annual cost rate in Chart 4 is yet another way to see how the aging of the U.S. population affects Social Security finances.

Chart 4: Projected Annual Cost and Income1 as a Percentage of Taxable Payroll

|

The Effect of Alternate Fertility, Mortality, and Immigration Assumptions

In addition to evaluating the Social Security program under different assumption sets and a probabilistic model, the trustees evaluate how the fertility, mortality, and immigration assumptions alone affect the program’s finances. The report shows that as the scope of fertility, mortality, and immigration rates unfold over the next 75 years, they will have an effect on long-term system finance. However, due to their delayed outcomes, variations in these rates over the next 25 years will not change the conclusion that the system will be unable to pay full benefits by the middle of next decade. Table 2 summarizes the results of the analysis.

Table 2: Adjusting Fertility, Mortality, and Immigration Assumptions; All Other Assumptions Are Intermediate

cannot be paid

annual decrease in adjusted death rates)

cannot be paid

cannot be paid

The short-term impact of fertility and mortality variations are intuitive—workers that will be available in the middle of next decade are already born, and future fertility rates will not change their number. Similarly, any increase or decrease in expected lifetimes will take many years to ripple through the system and will not change the outlook for the system as projected for the middle of the next decade.

Economic Issues

While the projected imbalance is driven primarily by demographics, the economy and the resulting wages that individuals earn will also have an effect on the sustainability of the system.

Taxable Payroll

The decline in the ratio of workers to beneficiaries would put less stress on the system if taxable payroll increased enough to offset the declining ratio. Unfortunately, increases in taxable payroll have not been enough, thus exacerbating the demographic problem.

Wages are a function of worker productivity,2 hours worked, growth in GDP, and the percentage of GDP that goes to taxable payroll. Table 3 shows the experience for these items from 2007 (the end of the last complete economic cycle) to 2019 as well as projection assumptions under the intermediate assumption set.

Table 3: Percentage Change in Real Wages and Components

Compensation

going to taxable wages

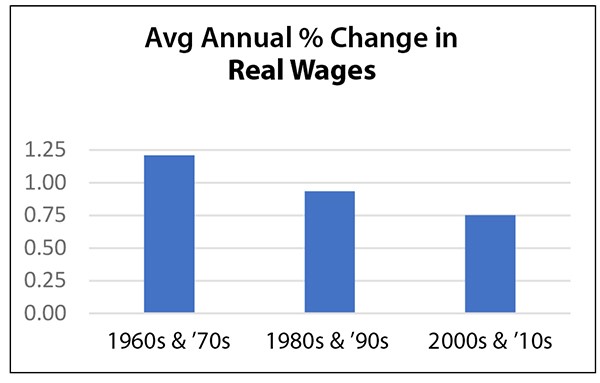

The following chart shows that the growth in real wages has decreased in the past six decades.

Chart 5: Annual Average Growth in Real Wages

|

If future gains in taxable payroll are less than expected, additional stress will be put on the system via lower-than-expected tax revenue. Lower wages will also result in lower benefits, but the payment of those lower benefits is far in the future, and the net result is a degradation of the system’s current actuarial deficit.

Effect of Health Care Premiums on Taxable Payroll

Employer-paid premiums for health insurance are not subject to Social Security payroll taxes under current law. These amounts have grown faster than wages in recent years, effectively suppressing the growth of taxable payroll. In late 2019, the excise tax on employer-sponsored group health insurance premiums above a specified level was repealed. The excise tax on employer-sponsored group health insurance premiums, along with anticipated competitive premiums from the Affordable Care Act (ACA) health benefit exchanges, were expected to slow the growth in the average cost of insurance, thus increasing the share of employee compensation provided in wages subject to the Social Security payroll tax. The trustees note that the repeal of the excise tax provision of the ACA will decrease the share of employee compensation that will be paid in wages covered by Social Security, resulting in slower growth in average real covered earnings and a negative financial effect on the OASDI program over both the short-range and long-range projection periods. The trustees estimate the repeal of the excise tax added 0.13 percentage points to the system’s 75-year actuarial deficit.

Effect of Low Interest Rates

OASDI trust fund assets consist entirely of special U.S. Treasury securities that are issued each year as needed to invest any surplus of income over outgo. The interest rate on these securities at issue is set by law and is equal to the average market yield on marketable interest-bearing securities of the U.S. federal government with four or more years to maturity. Over the past four decades, these interest rates have fallen significantly. Chart 6 shows the interest rates on new bond issues net of the rate of inflation for the year.

Note that the rates in Chart 6 are those on new bond issues. This rate generally varies from the actual return realized on the full portfolio of bonds held by the trust funds, which includes bonds issued over a range of recent years.

|

Chart 6: Real Interest Rates of New Issues

|

The trust fund assets are small compared to the value of all the benefits that Social Security pays. As a result, the effect of future interest earned by the trust fund is modest. As shown in Table 4 below, the current projected trust fund depletion date of 2035 is unchanged under the low-cost assumption for real interest rates and decreases slightly to 2034 under the high-cost assumption rate. On an ongoing basis, if rates over the next several decades continue to stay lower than in the past, system costs will increase marginally. For example, under the high-cost assumption rate of 1.8%, the 75-year actuarial deficit deteriorates by 0.20% of payroll (3.41% high-cost assumption vs. 3.21% intermediate assumption).

Table 4: Adjusting Real-Interest Rate Assumptions, All Other Assumptions are Intermediate

Cannot Be Paid

Rebalancing Social Security

Restoring balance to the Social Security system involves raising taxes, changing benefits, or finding a combination of these two approaches. Focusing on taxes alone, the table below shows that under the intermediate assumption set, an immediate combined employee/employer tax rate increase of 3.14% of taxable payroll (on top of the current 12.6% rate) is projected to be necessary to support all projected benefits under the current system over the next 75 years. The table also shows an immediate 19% cut in benefits for all current and future beneficiaries is necessary to balance the system over the next 75 years if taxes remain unchanged.

Table 5: Immediate Action to Achieve Solvency4

without change to tax rate

* A 3.14% increase implies a 1.57% increase for employees and a 1.57% increase for employers. Resulting rates would be 7.77% for employees and 7.77% for employers.

** If decreases were delayed to 2035, required benefit decreases would be 25%.

Table 5 shows the bookend options. The trustees note that lawmakers have a broad continuum of policy options regarding changes to the system, many of which combine changes to tax rates and benefits. It is important to note that changes in tax rates can be applied to all workers or a subset of workers. Likewise, changes to benefits can be applied to all beneficiaries or to a subset of beneficiaries. Readers may be interested in the Social Security game available on the American Academy of Actuaries website (“Try Your Hand at Social Security Reform”) to see how various policy options can be combined to restore balance to the system.

A Summary in Graphic Form

The graphic on the next page summarizes the Social Security system’s current imbalance. Today, taxes from the nearly three workers per retiree (along with revenue from benefit taxation and interest on the OASDI trust fund) are sufficient for the OASDI system to pay 100% of all benefits. By the middle of the next decade the number of retirees is projected to have grown much faster than the number of workers and the OASDI trust fund is projected to be depleted. At that point, the program revenue is projected to be sufficient to pay only 79% of all benefits due. Legislative changes, which range from raising taxes to cutting overall benefits (or some of both), are needed to correct the system’s imbalance.

|

A Word on Disability

The Social Security system also provides benefits to disabled workers. The system paid $145 billion to 10 million disabled beneficiaries and their dependents in 2019. Total system benefit payments in 2019 were $1,048 billion. Disability payments thus accounted for 14% of total system payments.

The number of workers applying for disability benefits has decreased materially since the 2008–2009 recession, so the near-term actuarial assumptions were adjusted downward in the 2020 Trustees Report to reflect that. The 2020 Trustees Report states that longer-term disability incidence is assumed to rise gradually from the current low levels to an ultimate age-sex-adjusted disability incidence rate of 5.0 per thousand by the end of the short-range projection period, a reduction from the 5.2 per thousand assumed in the 2019 report. By 2029, the trustees project that the percentage of total system benefits paid due to disability will drop from the current level of 13.8% to 10.7%. However, COVID-19 may impact disability claims, so we will have to wait until the 2021 report to learn more.

Technical Notes

The following notes apply to the entire issue brief.

- There are two trust funds in the Social Security system; one for disability benefits (DI Trust Fund) and the other for old-age and survivor benefits (OASI Trust Fund). Currently, each trust fund tracks revenue and expenses separately. The DI Trust Fund had been projected to run out of money in 2016 but Congress authorized the OASI Trust Fund to transfer money to the DI Trust Fund to prevent that from happening. This issue brief discusses the Social Security system as a whole (OASI and DI combined) under an assumption that Congress will continue to amend the law as needed to permit the transfer of funds between OASI and DI to stave off any shortfall in one trust fund or the other.

- Unless otherwise indicated, all numbers, charts, and tables are taken from 2020 Trustees Report.

- Unless otherwise indicated, the term “benefits” includes retirement, disability, and survivor benefits.

- Unless otherwise indicated, the term “income” includes revenue from payroll taxes and taxes on OASDI benefits as well as trust fund earnings.

- The intermediate assumption set reflects the trustees’ best estimates of future experience. Therefore, most of the figures in the Trustees Report and in this issue brief present outcomes under the intermediate assumptions only. The trustees report also present results under low-cost and high-cost alternatives to provide a range of possible future experience. The Trustees Report states that actual future costs are unlikely to be as extreme as those portrayed by the low-cost or high-cost projections.

- The trustees also look at OASDI finances under 5,000 independently generated stochastic simulations that reflect randomly assigned annual values for most of the key parameters. These simulations produce a distribution of projected outcomes and corresponding probabilities that future outcomes will fall within or outside a given range.

Appendix I

References

Annual Trustees Report and related Social Security Administration publications (Social Security Administration)

- American Academy of Actuaries Issue Briefs on Social Security

- Social Security—Automatic Adjustments (May 2018)

- Women and Social Security (May 2017)

- Helping the ‘Old-Old’—Possible Changes to Social Security to Address the Concerns of Older Americans (June 2016)

- Social Security Disability Program: Shortfall Solutions and Consequences (August 2015)

- Social Security Individual Accounts: Design Questions (May 2014)

- Quantitative Measures for Evaluating Social Security Reform Proposals (May 2014)

- A Guide to Analyzing Social Security Reform (December 2012)

- Means Testing for Social Security (December 2012)

- Understanding the Assumptions Used to Evaluate Social Security’s Financial Condition (May 2012)

- Significance of the Social Security Trust Funds (May 2012)

- Automatic Adjustments to Maintain Social Security’s Long-Range Actuarial Balance (August 2011)

- Raising the Retirement Age for Social Security (October 2010)

- Social Security Reform: Possible Changes to the Benefit Formula and Taxation (June 2010)

- Social Security: Evaluating the Structure for Basic Benefits (September 2007)

- Investing Social Security Assets in the Securities Markets (March 2007)

- A Guide to the Use of Stochastic Models in Analyzing Social Security (October 2005)

- Social Adequacy and Individual Equity in Social Security (January 2004)

|

[1] Excludes income from interest earned on invested trust fund asset reserves. [2] Productivity is defined as the ratio of real GDP to hours worked by all workers. [3] Intermediate assumption in 2007 Social Security Trustees Report. [4] The necessary tax rate increase of 3.14% differs from the 3.21% actuarial deficit for two reasons. First, the necessary tax rate increase is the increase required to maintain solvency throughout the period with a zero trust fund reserve at the end of the period, whereas the actuarial deficit also incorporates an ending trust fund reserve equal to one year’s cost at the end of the projection period. Second, the necessary tax rate increase reflects a behavioral response to tax rate changes, whereas the actuarial deficit does not. In particular, the calculation of the necessary tax rate increase assumes that an increase in payroll taxes results in a small shift of wages and salaries to forms of employee compensation that are not subject to the payroll tax. |

|

Craig Hanna, Director of Public Policy Members of the Social Security Committee include Ron Gebhardtsbauer, MAAA, FSA—Chairperson; Amy Kemp,MAAA, ASA, EA—Vice Chairperson; Janet Barr, MAAA, ASA; Gordon Enderle, MAAA, FSA; Margot Kaplan, MAAA, ASA, FCA; Eric Klieber, MAAA, FSA; Alexander Landsman, MAAA, FSA, EA; Jeffrey Leonard, MAAA, FSA, EA; Leslie Lohmann, MAAA, FSA, FCA, FCIA, EA; Gerard Mingione, MAAA, FSA, FCA, EA, CERA; and Brian Murphy,MAAA, FSA, FCA, EA. © 2020 American Academy of Actuaries. All rights reserved. |