| Issue Brief |

Understanding and Addressing Health Care Costs and Cost Growth in Medicaid: A Framework |

|

FEBRUARY 2020 |

|

Download a PDF version here. Key Points

|

- To reduce health care costs or cost growth, the current program or any proposal for Medicaid reform must accomplish one or more of the following: reduce the prices paid for services; reduce the utilization of services; shift to more cost-effective providers or services; keep high-risk/-cost patients healthier; increase beneficiary engagement; reduce program administrative (non-benefit) costs; reduce costs associated with waste, fraud, and abuse within the system; and/or reduce the number of individuals needing and/or eligible for the program.

- To evaluate public policy proposals to reform Medicaid, policymakers should consider how the proposals affect the cost of the program, how they affect enrollees’ access to care, how they affect the quality and outcomes of care received, whether they slow the growth in health care spending rather than shifting costs from one payer to another or increase uncompensated care, and whether they give providers and their patients incentives that encourage coordinated care to help control costs and improve quality.

- The Trump administration’s proposed fiscal year 2020 budget includes consideration for Medicaid block grants or per capita spending caps for Medicaid enrollees. While both approaches by design would shift federal financial responsibility/risk to the states in an increasing manner, their potential impact on overall aggregate Medicaid costs and cost trends remains unclear. Hence, block grants and per capita spending caps are outside this paper’s scope, and are better discussed elsewhere (see, for example, the Academy’s issue brief Proposed Approaches to Medicaid Funding).

Medicaid Cost Levels and Trends

The following table displays actual and projected Medicaid total dollar expenditures, on their own, and as a percentage comparison to National Health Expenditure (NHE) figures and to gross domestic product (GDP) figures. While it is always an imprecise exercise to project total health care costs years into the future, over a long horizon Medicaid’s growth has been, and is currently projected to be, substantial, now comprising almost 17% of health care spend, and approximately 3% of GDP.

2025/1990

1980, 1990 via National Health Expenditure Projections, 1994-2005

(Health Care Financing Review, Summer 1995, Volume 16, Number 4, page 234)

2015, 2025 via National Health Expenditure Projections, 2018-2027

(www.cms.gov, NHE Tables, 2/19)

It is very important to note that while the annual total dollar growth rate of 9.1% for the 35-year 1980 to 2015 time period is nominally high, 3.6% of that annual total was due to enrollment growth. Of the 7.3% annual total dollar growth rate for the 1990-to-2025 35-year time period, a similar annual 3.7% (so roughly half of the impact) is projected to be due to enrollment growth.

Note: These aggregate figures do not adjust for differing enrollment growth, mix, or cost growth levels exhibited by states and by the individual aged, disabled, children, adults, or the Affordable Care Act (ACA) newly eligible adult expansion populations.

Relatively consistent with the above, but indicative of more recent per enrollee cost growth slowing, Medicaid per enrollee annualized cost trends over the 10 years 2007–17 (half actual data, half projected) by enrollment category are roughly 3.2% for children and adults, and under 2.0% for aged and disabled.1

Aged and disabled individuals within Medicaid comprise approximately 23% of all enrollees but generate almost 55% of total program costs.2 The top 5% of the most costly individuals in Medicaid account for over 50% of total program costs.3

Medicaid recent annual growth percentages in per enrollee expenditures have compared very favorably to other health care systems such as Medicare and private health insurance.4 However, this differential is projected to be eliminated, perhaps by as early as 2020, and all programs per enrollee trends converge to a 4.7%-5.0% range in 2027. Medicaid actual and projected annual growth in per enrollee expenditures are:

2017 = 0.9% (lower than private health insurance at 4.0% and Medicare at 1.7%)

2018 = 1.1% (lower than private health insurance at 4.5% and Medicare at 3.1%)

2019 = 2.4% (lower than private health insurance at 3.9% and Medicare at 4.0%)

2027 = 4.8% (similar to private health insurance at 4.7% and Medicare at 5.0%)

Along with enrollment levels (as previously indicated, enrollment changes are a key factor in overall program growth, with enrollment trends increasing in times of economic decline), the projected per enrollee costs and trends fuel the incremental increases to projected Medicaid spending as a percentage of GDP. By enrollment category, consistent with the above, annual 2019-to-2026 per enrollee projected cost trends are:5

Aged = 4.0%

Disabled = 5.0%

Children = 4.8%

Adults = 5.1%

ACA Newly Eligible (Expansion) Adults = 5.1%

With a 5% annual cost trend, costs double (factor of 1.98) in 14 years.

On the national level, further granularity of component costs and trends, such as by category of service/provider type, and utilization relative to unit cost/price, can be much more difficult to analyze. This is due in large measure to the unique nature of each state’s Medicaid program, as well as the differing data and information sources used to manage their respective programs. However—and certainly with exceptions at the state, enrollment category, and category of service/provider type level—Medicaid cost trends generally appear to be driven by unit cost/price rather than utilization of services. This statement does not imply that utilization or unit cost/price levels are appropriate or inappropriate, only that in general cost trends are more driven by unit cost/price rather than utilization.

Of the service categories/provider types, high-cost specialty drugs within Pharmacy continue to be a driver, with multiple sources recording recent specialty drug unit cost/price trends in the high single-digits to almost-teens range. Facility (Hospital Inpatient, Hospital Outpatient, Emergency Room, Nursing Facility) unit cost/price trends also typically occur as drivers of overall claim cost trend given their large role within Medicaid and the significant negotiating leverage of facilities (particularly in many states’ at-risk managed care programs, where reimbursement levels are often higher than the state-defined fee schedules). For an example of utilization (and other residual factors) historical and projected trends, please see pages 43-50 of the 2017 Actuarial Report on the Financial Outlook for Medicaid.

|

Of course, normal annual statistical variation also applies, but other factors can also influence calculated cost trends, including those that should be held constant but could in fact be very difficult to hold completely constant. A theoretical example is dental coverage for children. A payer (state or health plan) might increase dental payment rates significantly in order to incentivize more dentists to participate in the program and/or to increase existing dental office hours. This action would not only increase analyzed dental unit cost/price, but would presumably increase utilization as well. Although these changes would show up in a trend analysis, this specific example could also easily be considered as a type of underlying program change adjustment. And if resulting better preventive dental care equates to better overall health, are higher-cost dental emergencies reduced down the road, let alone other non-dental health care costs? How are cost trends at that point in time then analyzed? |

|

|

Medicaid Background

Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that provides medical, behavioral health, and long-term care services to families and individuals with low income and limited resources or certain disabilities. The Medicaid program was created and signed into law in 1965 as part of Title XIX of the Social Security Act. In 1997, Congress, via Title XXI, authorized optional expanded coverage for children through the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Medicaid and CHIP are optional programs; however, all states, territories, and the District of Columbia currently participate in the programs. The federal government establishes minimum requirements for the programs while state governments manage the Medicaid and CHIP programs. Federal guidelines set forth program parameters and enable state governments to “customize” their Medicaid program via a number of waiver options to best serve their constituents.

Since 2002 Medicaid has increasingly covered more individuals than Medicare.6 Medicaid enrollment grew by over 23% from 2013 to 2017,7 driven by Medicaid coverage expansions in many states as a result of the ACA. During 2018 and 2019, Medicaid has seen overall enrollment decreases due to a combination of federal and state policy and administrative changes, as well as an improved economy. As of June 2019, Medicaid and CHIP provided health coverage to 72.2 million Americans,8 or approximately 22% of the U.S. population.

(While this paper uses “Medicaid” in its title, several, although certainly not all, of the described health care cost growth issues and challenges apply to CHIP as well.)

Funding of Medicaid is shared by the state and federal governments. The federal government funding (Federal Medical Assistance Percentage [FMAP]) varies by state, but is a minimum of 50% up to a maximum of 83% of total program costs. These figures include enhanced federal funding intended to incentivize specific services such as family planning and preventive care. The Office of the Actuary within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) projects the national average FMAP to be approximately 63% during 2019, up from 57% in 2000.9

The most significant change to Medicaid in recent history came in 2010 as part of the ACA. The ACA contains provisions that provide enhanced federal funding incentives for coverage to millions of adults who were previously uninsured, through Medicaid expansion. Initially, these provisions mandated the expansion of all state programs; however, the Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that the expansion program could be optional to states. If implemented by a state, under the expansion provision of the ACA, the federal government provides enhanced federal financial participation (FFP) to cover services for expansion enrollees. Expansion programs cover individuals with income effectively up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). Federal funding covered 100% of expansion service costs through the end of 2016. Funding decreased to 95% in 2017, declining until reaching 90% in 2020.

Medicaid expenditures are projected to be $623 billion in 2019, compared with $800 billion for Medicare.10 Medicaid expenditures have been summarized in four major categories: acute care fee-for-service (FFS) payments, long-term care FFS payments, capitation payments and other premiums, and disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments. For the first time in program history, 2013 expenditures on capitation payments and other premiums exceeded acute care FFS payments, illustrating the ever-continuous movement to at-risk Medicaid managed care.11 On a per enrollee basis, projected 2019 annual Medicaid costs vary from almost $4,000 for children to almost $22,000 for those disabled.12

Medicaid Populations Covered

Medicaid coverage includes more than two dozen mandatory eligibility groups, as well as several optional groups.

Approximately 45% of current Medicaid program enrollees are children. Medicaid serves almost 30 million children, and together with CHIP cover approximately half of the U.S. population age 18 or under. Although the federal government only requires Medicaid programs to cover children with family income effectively up to 100% of the FPL, most states have voluntarily chosen to extend coverage to more children. Forty-nine state Medicaid and CHIP programs cover children up to at least 200% of FPL (19 states at least 300% of FPL).13

Another important population served by Medicaid is pregnant women. Medicaid covers almost half of the pregnant women in the U.S., similar to the proportion of children, and funds approximately 2 million births annually.14

Medicaid program rules require states to provide Medicaid coverage to low-income adults who are caretakers for children. In states that have chosen not to expand Medicaid, income standards for adult caretakers could be as low as 17% of FPL.15 In states that have chosen to expand Medicaid, low-income adults up to 138% FPL are eligible for Medicaid, and coverage is not dependent on whether the adult is caring for children or not.

Medicaid also provides critical support to low-income seniors and individuals with disabilities, assisting nearly 6 million seniors and nearly 11 million individuals with disabilities.16 Nearly all of the seniors and almost half the non-elderly individuals with disabilities are also enrolled in Medicare, and thus are “dually eligible.”

Because Medicare coverage for long-term care is limited, both in scope and duration, it falls to Medicaid to serve as the nation’s long-term care safety net provider. Medicaid is the primary payer for 63% of nursing home enrollees.17 In addition to the aged, Medicaid provides long-term care services and supports (LTSS) to low-income disabled persons, developmentally disabled persons (those with mental or cognitive conditions too severe to allow full independence), and those who are mentally ill or suffer from addiction. In most states, LTSS may be provided in either an institutional setting or in a variety of home and community-based settings.

Medicaid Benefits Covered

Compared to private health insurance plans, Medicaid benefits are quite comprehensive, and typically have very limited cost-sharing. On the other hand, access to providers could be an issue for some Medicaid enrollees, especially where provider reimbursement is low. States are each permitted to design their own benefit packages, within broad guidelines. Federal law designates certain services as “mandatory” and others as “optional.” There are 15 broad categories of mandatory Medicaid benefits. Key mandatory and optional services include:18

|

Mandatory benefits

Inpatient hospital services

Outpatient hospital services

Nursing facility services

Home health services

Physician services

Laboratory and X-ray services

FQHCs and RHCs

Family planning services

Transportation to medical care

Nurse practitioner, nurse midwife, and freestanding birth center services

|

Optional benefits

Prescription drugs

Therapies: physical, occupational, speech, hearing and language, and respiratory care

Podiatry services

Optometry services and eyeglasses

Dental services and dentures

Chiropractic services

Hospice

Durable medical equipment and prosthetics

Personal care services

Home and community-based (HCBS) long-term care services and supports (LTSS)

|

Certain mandatory benefits are unusual outside of the Medicaid market. For example, nursing facility services and home health services are not duration-limited within Medicaid but can be limited in Medicare or the private insurance markets. Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) have traditionally played a key role providing primary care to all, regardless of ability to pay, and are specifically named in Section 1905 of the Social Security Act. Transportation to medical care includes both emergency services, such as by ambulance, and non-emergency transportation, such as taxi or bus service to a routine office visit. This is to ensure that important medical services such as prenatal care or vaccinations are not missed due to inability to travel to the doctor’s office.

The most surprising optional benefit is probably prescription drugs given its broad importance. However, this benefit is covered by all the states and territories and was required in the alternative benefit plans provided to the new adult group under Medicaid expansion. Home and community-based LTSS may be optional but is generally a cost-effective alternative to nursing facility care, which is mandatory.

Optional benefits such as dental or vision care are sometimes not covered for adults, but these and other optional benefits are mandatory for children up to age 21 under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, which requires that states provide children with all services needed to correct or ameliorate any health condition.

States are also given latitude in determining what constitutes medical necessity, and the amount, duration, and scope of care provided for most mandatory and optional services. Most states document these decisions in a medical policy manual that is updated periodically.

Under Section 1916(a) of the Social Security Act, over half of Medicaid enrollees are exempt from all cost-sharing, including children and most pregnant women. For other enrollees with income below 100% FPL, cost-sharing is limited to “nominal amounts,”19 and services may not be withheld from those who cannot or will not pay. Cost-sharing may be imposed on non-exempt enrollees with income over 100% FPL or those covered under a Section 1115 of the Social Security Act demonstration waiver.

Medicaid Care Delivery System Models

A state may use one or multiple care delivery system models.20 On the value spectrum of access to, quality of, and cost associated with care, all models have strengths as well as opportunities for improvement. Care delivery system and payment/reimbursement models are not one and the same, but it is important to realize that one outcome of desirable care delivery is a longer-term reduction in the cost trajectory of health care. A number of distinct care delivery system models are being used. The ACA has accelerated Medicaid innovation with regard to care delivery system models, as new funding opportunities for delivery system initiatives have become available.

When their programs began, the vast majority of states operated Medicaid under an FFS model. This is an open-access system for beneficiaries (to providers willing to contract with the Medicaid agency). Medicaid reimburses these providers on an FFS basis. The challenges of this delivery system and payment model are well known: fragmented care, with a lack of care coordination and medical management within the delivery system, payment based on volume (number) of services provided, leading to implied incentive for overutilization, and limited or no measurement of quality or outcomes. While state administrative costs under an FFS model can be relatively low, given the above concerns a large number of states have moved away from FFS, either strongly supplementing it or shifting to more formal managed care models.

Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) is a care management program that states have used since the 1980s. These programs have typically involved paying primary care providers a modest per person monthly fee to provide, coordinate, and monitor care for a limited number of services. Providers must meet certain requirements to participate and are responsible to oversee care of enrollees who are assigned to them or who self-select. Some programs have since been expanded to include a wider array of services. These programs are referred to as Enhanced Primary Care Case Management (EPCCM). Neither of these programs put providers at financial risk and there are, therefore, inherent limitations on their impact on other service categories.

Many states have contracted out the care delivery and financial risk to risk-based managed care, including Managed Care Organizations (MCOs). Some services might be carved out from the MCO’s risk. Historically, for example, behavioral health has often been carved out, although there is a trend toward integrating behavioral health and physical health services. An MCO can be a traditional health maintenance organization or a health insurer, or a “staff model” where physicians and other providers are employees of the MCO. MCOs can also subcontract some services to Prepaid Health Plans (PHPs), or even other MCOs. Direct state contracting with PHPs is another option. These plans are at risk for a limited number of services. Prepaid Inpatient Health Plans (PIHPs) provide inpatient hospital or institutional services, such as inpatient behavioral health care. Prepaid Ambulatory Health Plans (PAHPs) provide outpatient services, such as dental services. MCOs, PHPs, PIHPS, and PAHPS are paid a predetermined per-member-per-month capitation payment.

Considerably less common at this point than at-risk managed care for physical or behavioral health, managed care for long-term services and supports has recently seen an uptick in adoption in some states (although Arizona’s Medicaid program began managed long-term care in the late 1980s). Managed Long-Term Services and Supports (MLTSS) programs usually include Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS), which generally provide significant savings opportunities to traditional institutional care services. The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE)21 is another long-term care managed care program that provides comprehensive medical and social services to certain frail, community-dwelling elderly individuals, most of whom are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Individuals can join PACE if they meet certain conditions: 1) are age 55 or older, 2) live in the service area of a PACE organization, 3) are eligible for nursing home care, and 4) are able to live safely in the community.

A Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) is a relationship-based team model that is intended to support primary care physicians in leading care coordination for a population. It focuses on patient contact and a whole-person orientation. Many PCMH models have had significant focus on higher-risk populations. The Medicaid Health Home (HH) model builds on the PCMH concept. Established by the ACA, Health Homes are designed to coordinate care for a high-risk population with multiple chronic conditions. States receive(d) 90% FMAP for HH programs (for up to eight quarters).

An Accountable Care Organization (ACO) is a group of health care providers that voluntarily agree to accept risk and share responsibility for coordinated delivery and outcomes for a defined population. Like other managed care entities, ACOs are expected to generate efficiency and savings by reducing unnecessary utilization and managing care. ACOs generally include primary and specialty care providers and at least one hospital. Financial incentives to ACO providers are generally a share of the savings produced relative to a predetermined benchmark.

A care delivery system enhancement strategy is a shift to avenues of easier access to care with resulting use of qualified, yet lower cost, providers. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants have provided additional opportunities for care, particularly in areas with primary care physician shortages. Retail clinics are also accessible choices that usually do not require an appointment in advance. Telemedicine/telehealth involves the communication of medical services from a remote site. For Medicaid recipients, this can be a valued service for rural residents and individuals with particular transportation challenges.

Medicaid Payment/Reimbursement Models

A state might use one or multiple payment/reimbursement models.22 Payment/reimbursement models typically are within individual care delivery system models, but in some cases could be alongside them, supplementing the entire system. As with care delivery system models, all payment/reimbursement models have strengths as well as prospects for improvement.

As discussed earlier, an FFS payment/reimbursement model pays providers for the services they deliver, independent of quality of care or outcomes. A provider’s only financial risk is if the fee levels are not adequate to cover costs. Fee levels are determined by schedules set by the state (under an FFS or PCCM care delivery system model) or negotiated by a health plan (under at-risk managed care models). Aggregate health care costs are determined based on the number of procedures performed, tests ordered, drugs prescribed, and admissions authorized applied to the appropriate fees.

A Case/Care Management Fee is generally paid to providers who provide and coordinate care within PCCM, EPCCM, PCMH, or HH medical programs. These per member per month add-on fees are sometimes adjusted for member demographics or measured health care risk.

Capitation is the traditional payment model used with at-risk MCOs, PHPs, PIHPs, PAHPs, and ACOs for the risk of managing the care, and the cost, of a population. Capitation rates are generally determined on an annual basis; rates are often developed unilaterally by states, while other states procure services through a competitive bidding process. Capitation rates are almost always on a per member per month basis and adjusted for demographics and aid category. Often risk adjustment by a model developed for a Medicaid population is involved to incrementally better match payment to the health risk of the population enrolled in a specific plan.

Pay-for-Performance (“P4P”) rewards providers or health plans for achieving or exceeding specified quality benchmarks or other goals. P4P can be a stand-alone payment model or it can be incorporated into other payment models. As an example, a percentage withholding could be applied to a capitation payment, with partial or full return of withheld funds based on certain quality metrics being partially or fully realized. Conversely, a bonus payment above the capitation rates could be paid for partially or fully meeting greater-than-expected levels of specified goals. Developing and measuring P4P metrics is an involved process.

Some states use a shared savings model within their Medicaid program. This model was formalized in the Medicare program—the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP). Two variations of this type of model exist.

- In a gain-sharing model, providers (or other organizations, e.g., ACOs) share in savings measured from a specific population over a fixed period of time. Actual costs are compared to a pre-established benchmark that is usually determined from historical experience. Performance and quality requirements may also be necessary to realize any incentive payments. Providers in a gain-sharing model do not assume any downside risk.

- In a risk-sharing shared savings model, providers assume downside risk along with the opportunity to realize upside incentive payments. There are usually limits to the amount of risk assumed by providers in this model. There could be stop-loss provisions for large claims above a certain level.

Shared savings models are often used as a transition vehicle for providers moving from FFS payment to capitation.

Bundled payments are episode-based payments wherein providers are reimbursed for each episode but assume risk for the treatments provided within each episode. This payment model is also viewed as a potential transitional model with partial provider risk. In this model, providers benefit from developing efficiency within episodes. Bundled payment models are increasing in popularity, perhaps at least partially due to Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement23 initiative. Episode of care bundled payments often manage costs over a 30- or 90-day horizon. Global bundling is a longer-term arrangement (often one year) where risk-adjusted payments are usually provided for a wide range of services. Given the longer time horizon, global bundling payments often incorporate quality or outcome measures that impact the amount of the payment.

Delivery System Reform Incentive Payments (DSRIP)24 are Medicaid waiver initiatives that allow states to experiment with performance-based payment models to hospitals and other providers. Eligibility for DSRIP funds is contingent on those providers meeting certain performance metrics. While the exact structure and requirements of DSRIP initiatives vary, there is often a focus on meeting process-oriented metrics in the early years of the waiver, such as metrics related to infrastructure development or system redesign, and a focus on more outcome-oriented metrics in later years. For example, infrastructure-related metrics might pertain to implementation of chronic care management registries or enhanced interpretation services. System redesign metrics might relate to expansion of medical homes or physical and behavioral health care integration. Outcome measures might address clinical care or population health improvements.

“Value-based” payments or purchasing has become an increasingly popular concept, with high focus both from states and from CMS. Value-based models seek to shift provider payments and incentives from volume to efficiency and quality care delivery, generating patient health improvements. To a significant degree, many of the payment/reimbursement models described above are currently value-based, or could become such with some level of modification. Value-based model development is accelerating and includes new government incentives and requirements, clinical integration within the care delivery system, enhanced data mining and analysis capabilities, increased transparency, and refinement of risk adjustment models.

Cost and Trend Drivers

While Medicaid’s unique “safety net provider” role generates several cost and trend issues specific to it, many of Medicaid’s health care cost and trend growth drivers are also major concerns within the larger U.S. health care system including private health insurance, Medicare, or both. These universal issues include (but are not limited to), in no particular order:

- Less-healthy lifestyles such as poor eating habits and lack of exercise and sleep lead to greater levels of obesity and a multitude of other health problems. Although on the decline, smoking has both short- and long-term implications on an individual’s health.

- Aging of the population, along with changes in relative socioeconomic position (education, occupation, income) and social relationships, has an impact.

- Mental health and substance use issues (for example, opioid abuse) affect all income stratifications.

- Several of the current care delivery system and payment/reimbursement models reward more tests and procedures (discussed in previous respective sections).

- More expensive medical technology drive prices/unit costs ever higher (examples include catastrophic admissions—neonatal intensive care unit [NICU] cases and the associated high-level technology can routinely run in the hundreds of thousands of dollars—and Breakthrough Therapy Designation [BTD]/Specialty drugs being developed and utilized). The Academy’s Medicaid Subcommittee BTD letter of November 11, 2014, to CMS titled “Potential approaches to address the challenges posed to Medicaid capitation rates by Breakthrough Therapy Designation medications, including Sovaldi for Hepatitis C” summarizes significant, still relevant, concerns.

- Broad(er) provider network requirements (for other than state FFS/PCCM care delivery systems) limit pricing discount opportunities. While broad(er) networks increase consumer choice and access, narrow(er) networks provide increased contracting leverage for the health plan with a higher concentration of members using the more limited network of providers.

- Provider consolidation can bring many benefits, but the larger entity might have greater leverage in contract negotiations, thus exerting upward price pressure.

- Pent-up demand (short-term impact, driven by new eligibility or benefits) has a very real, yet very difficult to measure, impact on health care cost and trends. When something new becomes available, the natural tendency is to utilize the newly available services.

- Excessive administration (non-benefit) levels, along with increases in regulations and requirements, taxes, and fees, further increase health care program (including Medicaid) costs.

- Waste, fraud, and abuse (see discussion below) have an impact as well.

Several of these systemwide health care cost and trend divers were described in a May 2014 Academy Essential Elements brief titled, “What Drives the Growing Cost of Health Care?”

Other health care cost and trend drivers are more specific to Medicaid. They include25 (but are not limited to) in no particular order:

- Social determinants of heath. Lack of adequate food, housing, education, community supports, economic security, etc. negatively impact an individual’s or family’s health.

- Low or no cost-sharing/out-of-pocket costs increase the potential for excessive utilization of services. Given no or low income levels for the Medicaid population, it is critical there be a balance between a reasonable cost-sharing amount or percentage and that amount not being so onerous that needed benefits are not accessed due to an individual’s available funds being prioritized elsewhere.

- Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are additional amounts paid to hospitals that serve a disproportionally large number of Medicaid or uninsured patients. These payments could be subject to a hospital-specific limit. An annual allotment to each state limits FFP in these payments. Given increased coverage under the ACA that resulted in lower numbers of those uninsured, DSH allotments were scheduled to be decreased. This scenario can put increased pressure on Medicaid program costs if the numbers of uninsured do not decrease at the level projected in the DSH allotment decreases, and providers attempt to negotiate higher non-DSH reimbursement.

- Intergovernmental Transfer (IGT) is a transfer of public funds between governmental entities (for example, county government to state government or state university hospital to state Medicaid agency). IGTs are an allowable funding mechanism (within limits) used to help draw down additional federal funding without commensurate state general fund involvement. The provider is funding the non-federal share so it doesn’t hit the state budget.

- Special/supplemental payments from provider assessments/fees/taxes are in addition to regular Medicaid payment amounts, and may be made by states directly or through health plans to providers of Medicaid services. These payments are usually made to hospitals, but other provider types can also qualify for such payments. These payments are sometimes reciprocation for the provider paying a special tax or assessment fee. When special/supplemental payments are considered, Medicaid hospital payments can be similar to/exceed Medicare levels.26 CMS, through the May 2016 Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule, is phasing out “pass-through” payments, although states and CMS are working to develop acceptable alternatives. Absent such alternatives, additional cost pressure in other payment/reimbursement areas are likely.

- Upper Payment Limit (UPL)27 payments are supplemental payments that comprise the difference between Medicaid payments for services and the maximum payment level allowed under the UPL for those services. Designed for FFS programs and primarily, although not exclusively, used to supplement hospital payments, they have become more prevalent in managed care via Section 1115 waivers.

- Provider or health plan assessments, fees, or taxes increase program costs (although in some cases net funding comes back to the state).

- The concept of selection can be a driver of per capita costs. As states and the federal government make changes to eligibility systems and processes, add/increase premiums, introduce work requirements, vary their promotion of the program, etc., these changes can have an impact on the mix of enrollees, or proportion of higher-cost enrollees remaining in the program, which can drive per capita cost changes. Impediments to enrollment directly reduce enrollment, and thus overall costs, but given the above also tend to result in higher growth in per capita costs. The opposite result can clearly happen if eligibility processes are streamlined.

- Pharmacy rebates actually decrease program costs, but limited or slow data collection and submission can result in a missed or reduced opportunity to minimize net pharmacy costs.

Reducing or eliminating items such as IGTs, special/supplemental payments, UPLs, or assessments/fees/taxes, etc. impact provider revenue streams, which would put increased pressure on other Medicaid program costs. These types of Medicaid payments are very complex, and changing them are clearly not easily undertaken and accomplished. There are downstream implications regarding cost-shifting and state/federal revenue sources that must be carefully considered and analyzed.

Waste, Fraud, and Abuse in Medicaid

Health care system waste, fraud, and abuse remains an ongoing national concern, and their respective impacts unquestionably contribute to higher Medicaid cost levels. CMS, based upon an Office of Management and Budget (OMB) analysis of improper payments (which include, but are not limited to, waste, fraud, and abuse), estimated the impact to be slightly over 5 percent of Medicaid program cost.28

CMS provides exhaustive topic resources on its website under “Medicaid Program Integrity Education.” In its booklet Fraud, Waste and Abuse Toolkit—Health Care Fraud and Program Integrity: An Overview for Providers, CMS provides definitions of each of the terms:

Waste (not defined in Medicaid rules) is “generally understood to encompass over-utilization, underutilization or misuse of resources, and typically is not a criminal or intentional act.”

Abuse is defined in Medicaid rules as follows:

“… provider practices that are inconsistent with sound fiscal, business, or medical practices, and result in an unnecessary cost to the Medicaid program, or in reimbursement for services that are not medically necessary or that fail to meet professionally recognized standards for health care. It also includes beneficiary practices that result in unnecessary cost to the Medicaid program.”

The booklet goes on to note that “a provider can abuse the Medicaid program even if there is no intent to deceive; however, fraud involves intent.”

Health care fraud can be committed by providers, beneficiaries, corporate officials, and others. The rules governing Medicaid define “fraud” as follows:

“… an intentional deception or misrepresentation made by a person with the knowledge that the deception could result in some unauthorized benefit to himself or some other person. It includes any act that constitutes fraud under applicable Federal or State law.”

With the CMS 5% “improper payments” estimate, a 20% reduction (to 4%) would save Medicaid more than $6 billion annually.

Approaches to Positively Impacting Medicaid Health Care Cost Levels and Growth

While there are clearly no magic pills or silver bullets to dramatically and immediately reduce Medicaid cost levels or trends under current population and benefit levels, there are just as clearly a multitude of approaches that individually and collectively could provide substantial impacts.

From a big-picture standpoint, the Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network (LAN) has developed a readily understandable and comprehensive framework around alternative payment models (APMs) currently in place, and perhaps to be developed. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 2015 created LAN to help drive work on “value instead of volume” already being done in the private insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare programs.

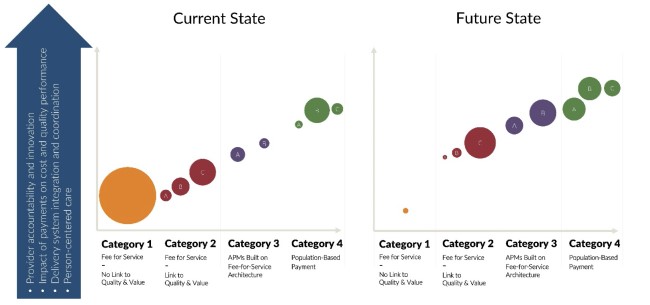

The first graphic below reflects the LAN underlying framework, including four categories of payment/reimbursement models, each with specific model strategies. Delivery system is technically not specifically mentioned except in the fourth category, although delivery system, as mentioned above, can have positive effects on the care provided as well as the total cost.

|

The second graphic includes circles that are meant to reflect spending size within the various categories. Although the circle size spending values in the “Current State” and “Future State” graphic are not based on Medicaid, they certainly can represent desired change over time reflecting increasing movements from Category 1 and Category 2 into categories 3 and 4. And the graphic shows desired movement within individual categories to a higher level of value-based care, “A” to “B” and “B” to “C.”

|

Clearly state Medicaid programs need to choose which category (1-4) and which level (A-C) are the best long-term fit given their unique circumstances, albeit with consideration of market dynamics such as provider readiness. There is no wrong answer. However, to reiterate the second and third Key Points at the introduction of this framework paper, a potential goal for future consideration by each state Medicaid program would be to target movement along the spectrum of increasing value-based care, as illustrated below.

Underneath the big-picture framework outlined above, there are, of course, a multitude of medium and smaller-sized initiatives and approaches that can impact Medicaid health care cost levels and cost growth trends. They include (but are not limited to) in no particular order:

- Increase personal/shared responsibility for care decision-making and outcomes, which can involve increased cost-sharing (premiums/copayments/deductibles/coinsurance) or concepts such as health savings accounts. Appropriate balance should be maintained, as no-/low-income individuals might prioritize other items such as food and shelter in relation to health care, which could jeopardize coverage or result in low(er)-intensity services such as primary care visits being replaced with high(er)-intensity services such as emergency room visits.

- Expand systemwide resources and data analyses and edits designed to reduce health care waste, fraud, and abuse to the extent possible/practicable. These could include eligibility analyses and audits, enhanced provider credentialing, enhanced front-end controls, and post-payment claim reviews and audits (examples include duplicate payments, improper billings, upcoding, compound prescriptions review, review of certain preventable higher-cost imaging and radiology as well as hospital admissions/readmissions, and payment adjustments for Hospital Acquired Conditions).

- Focus on the use of managed care principles exhibited within the care delivery system models, payment/reimbursement models and LAN category payment models outlined. (As more membership moves from an unmanaged environment to more-managed Medicaid, utilization levels for office visits and pharmacy services may increase, while utilization levels for higher-cost emergency room visits and hospital admissions would presumably decrease.)

- Use managed care techniques to better coordinate care and engage beneficiaries. (Examples include expansion of telehealth services, intensive care coordination, chronic care management, focus on preventive care in general and on items such as early elective deliveries, assistance in finding housing, drug/alcohol rehabilitation program enrollment, and providing assistance in access to services/making appointments with primary care doctors. Could involve working directly with social support programs.)

- Work to overcome regulatory and operational challenges associated with incorporation of those social determinants of health (SDOH) conditions and situations whose addressing may be cost-effective for Medicaid. There is considerable literature on SDOH. An excellent reference with regard to Medicaid is The Commonwealth Fund’s January 2018 practical strategies document, Enabling Sustainable Investment in Social Interventions: A Review of Medicaid Managed Care Rate-Setting Tools.

- Continue prioritized focus on prescription drug spending on multiple fronts, including but not limited to:

- Evaluation/benchmarking of Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) contracting (if applicable),

- Increased use of generic medications, generics-based formularies, and Medicaid-specific maximum allowable cost lists,

- Increased use of 340b pricing if available (certain providers, such as FQHCs, often have access to 340b pricing),

- Increased utilization management (quantity limits, prior authorization) where available,

- Benchmarking against other pharmacy pricing standards, Develop narrow(er) or specialty networks where allowed,

- Regularly re-evaluate the formulary for each drug class, Consider development of pharmacy incentive pools,

- Work with drug manufacturers and/or health plans to maximize rebates via applicable documentation and timely collection, and

- Consider outcomes-based alternative payment models for high cost drugs via contracts with pharmaceutical manufacturers themselves.

- Explore integration of programs such as shared savings programs for individuals dually eligible under Medicare and Medicaid, or integration of services such as combinations of mental/behavioral health, physical health, and long-term services and supports.

- Pursue/continue progress in rebalancing home-and-community-based services and institutional care toward the home-and-community-based setting.

- Enhance subrogation efforts for third-party recoveries. Either develop the desired expertise in-house or contract with a specialized vendor.

- Incorporate best practices regarding administrative (non-benefit) costs. Increased regulations, reporting, and monitoring/oversight put upward pressure on administrative expenses, yet material variations remain state by state and health plan by health plan.

- Increase use and frequency of competitive bidding in at-risk Medicaid managed care, if applicable.

Conclusion

Options to address Medicaid spending include efforts to increase beneficiary engagement and in some cases financial responsibility, along with increased provider and health plan and/or state (block grants/per capita spending caps) financial responsibility (e.g., the provider/health plan/state aspect often in combination with increased alignment of incentives to encourage more effective use of care, with quality outcomes). Efforts to eliminate waste, fraud, and abuse and to use managed care techniques to better coordinate care are vital, as are the myriad suggested examples itemized over the previous pages.

When evaluating approaches to reduce costs and slow spending growth in Medicaid, it is important to recognize that improving the sustainability of Medicaid also requires slowing the growth in overall health spending rather than shifting costs from one payer to another or increasing uncompensated care. As potential reforms to Medicaid are considered, it is important to evaluate the effect those reforms could have on the viability of the Medicaid program, including cost, access, and quality of care.

Craig Hanna, Director of Public Policy Members of the Medicaid Subcommittee, which authored this issue brief, include Julia Lerche, MAAA, FSA—Chairperson; Christine Bach, MAAA, ASA; Yolanda Banderas, MAAA, ASA; Damian Birnstihl, MAAA, FSA; Manoj Bista, MAAA, FSA; Yekaterina Bogush, MAAA, FSA; Jill Bruckert, MAAA, FSA; April Choi, MAAA, FSA; Adrian Clark, MAAA, FSA; Michael Cook, MAAA, FSA; Robert Damler, MAAA, FSA; Peter Davidson, MAAA, FSA; Mathieu Doucet, MAAA, FSA; Timothy Fitzpatrick, MAAA, ASA; Kevin Geurtsen, MAAA, FSA; Sabrina Gibson, MAAA, FSA; Robert Hastings, MAAA, ASA; Marlene Howard, MAAA, FSA; Ernest Jaramillo, MAAA, ASA; Shereen Jensen, MAAA, FSA; Craig Keizur, MAAA, FSA; Don Killian, MAAA, FSA; Joshua Kuai, MAAA, FSA; Jinn-Feng Lin, MAAA, FSA; Han Lu, MAAA, ASA; Benjamin Lynam, MAAA, FSA; Karen MacDonald, MAAA, FSA; Marilyn McGaffin, MAAA, ASA; John Meerschaert, MAAA, FSA; James Meidlinger, MAAA, FSA; Christine Mytelka, MAAA, FSA; Donna Novak, MAAA, ASA, FCA; F. Ronald Ogborne, MAAA, FSA, CERA; Rebecca Owen, MAAA, FSA, FCA; Jeremy Palmer, MAAA, FSA; Chieh Pan, MAAA, ASA; Susan Pantely, MAAA, FSA; Bela Patel-Fernandez, MAAA, FSA; Michelle Raleigh, MAAA, ASA; Jonathan Rosenblith, MAAA, ASA; F. Kevin Russell, MAAA, FSA; Sujata Sanghvi, MAAA, FSA; Colby Schaeffer, MAAA, ASA; Jaredd Simons, MAAA, ASA; Martin Staehlin, MAAA, FSA; Kathleen Tottle, MAAA, FSA; Jianbin Xu, MAAA, FSA; Rodger Yan, MAAA, FSA; and Xuemin Zhang, MAAA, ASA. The subcommittee wishes to thank Mike Nordstrom, MAAA, ASA. |