| Issue Brief |

Surprise Medical Bills:An Overview of the Problem and Approaches to Address It |

|

SEPTEMBER 2019 |

|

Download a PDF version here. Surprise medical billing can happen when someone seeks care at an in-network facility such as a hospital but inadvertently receives some services from providers who are out-of-network. In these circumstances patients risk higher bills, largely because out-of-network providers can balance-bill patients for any differences between their charges and what the health plan pays. In addition, patients typically face higher deductibles, coinsurance, and out-of-pocket limits for out-of-network services. These higher cost-sharing requirements are intended to provide patients incentives to use in-network providers but can penalize patients receiving out-of-network care unknowingly and through no fault of their own. Surprise-billing instances may be a relatively small share of all health care encounters, but the consequences can be considerable for those patients affected. As a result, policymakers are seeking to address the problem by looking at ways of limiting the amount that consumers have to pay out of pocket for surprise bills and by setting up mechanisms for determining what out-of-network providers will be paid by insurers. This issue brief provides an overview of the surprise-billing problem and provides insights on approaches to address it. The problem has arisen in large part because certain medical professionals, such as emergency room doctors and ancillary service providers, have less incentive to negotiate discounted rates or join a network in order to guarantee patient volume. Most surprise-billing proposals would hold consumers harmless; they would prohibit balance billing and base patient cost-sharing on in-network cost-sharing requirements for services provided at an in-network facility. Where they differ is how providers would be paid. Some proposals would set payment benchmarks, based for instance on median in-network provider rates or some multiple of Medicare rates. Others would use a dispute resolution process, such as arbitration, either instead of or in addition to setting payment benchmarks.1 Setting payment benchmarks below the average in-network rate could lead to lower provider payments and premiums, and could also provide an incentive for providers to join a network. An arbitration process could put downward pressure on provider rates, provided it includes guardrails such as incorporating an appropriately low default payment rate and a reasonable range of payment offers. Rather than applying arbitration in all surprise bill situations, arbitration could be used to supplement a payment benchmark in rare instances only. Regardless of the option, using provider charges as the basis for provider payment could lead to even higher provider charges and increased incentives to be out of network. |

Overview

Numerous studies have examined the incidence of potential surprise bills,2 their causes, and state-level efforts to address them. Findings include:

- One in five inpatient admissions from the emergency department can lead to surprise bills.3 Ambulances and air or water ambulances have an even greater risk of resulting in a surprise bill, with more than half being furnished by out-of-network providers (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1: Share of Visits Leading to Potential Surprise Medical Bills, 2014

Source: Christopher Garmon and Benjamin Chartock, “One in Five Inpatient Emergency Department Cases May Lead to Surprise Bills,” Health Affairs 36:1 (177-181 and online web appendix), January 2017 (accessed August 26, 2019).

- The rate of potential surprise bills appears to be increasing over time.4 According to data from a large insurer, the rate of receiving some out-of-network care (including from an out-of-network ambulance) during an emergency visit to an in-network facility increased from 32% in 2010 to 43% in 2016 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Source: Eric C. Sun, Michelle M. Mello, Jasmin Moshfegh, and Laurence C. Baker, “Assessment of Out-of-Network Billing for Privately Insured Patients Receiving Care in In-Network Hospitals,” JAMA Internal Medicine, August 12, 2019 (accessed August 26, 2019). |

Similar increases occurred among inpatient admissions. At the same time, the median patient’s potential out-of-pocket cost for the out-of-network care more than quadrupled for care received during an emergency visit, from $107 to $482, and more than tripled for an inpatient admission, from $285 to $984. Out-of-pocket costs for some patients could be even higher. For instance, in 2016, 25% of patients receiving out-of-network care during an inpatient admission could have faced out-of-pocket costs of at least $2,000 and 10% could have faced out-of-pocket costs of at least $4,000.

- Out-of-network billing has been fairly concentrated among certain hospitals.5 In 2015, half of all hospitals had out-of-network billing rates for emergency department physicians of 2% or less, meaning their emergency department patients were unlikely to receive a surprise bill. In contrast, 15% of hospitals had out-of-network billing rates for emergency physicians higher than 80%; patients treated at these hospital emergency departments were very likely to receive a surprise bill. Notably, out-of-network billing rates were found to increase dramatically upon the entry of an emergency department physician-outsourcing firm.

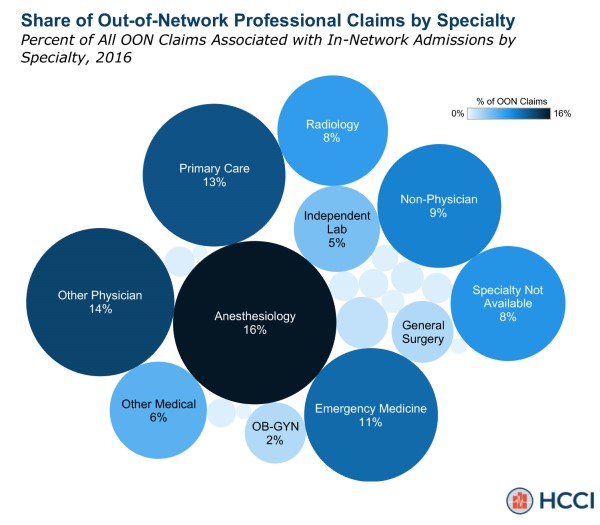

- Particular specialties represent larger shares of out-of-network claims.6 Among in-network inpatient admissions, anesthesiologists make up 16% of out-of-network claims (Figure 3). Other specialties making up large shares of out-of-network claims include primary care (13%), emergency medicine (11%), non-physician (9%), and radiology (8%).

FIGURE 3

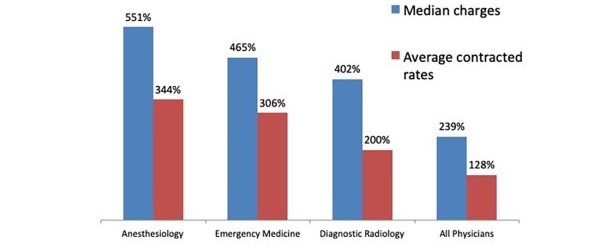

- Payment rates for emergency room and ancillary physicians are much higher than other specialties. Patients can usually choose their hospital, but they have little to no control over their emergency room doctor or ancillary service providers, such as anesthesiologists, radiologists, and pathologists. As a result, these doctors don’t need to negotiate discounted rates or join a network to guarantee patient volume. Payment rates for these specialties are much higher, relative to Medicare rates, than for other physicians that patients have a more direct role in choosing, even if they have contracted to be in network (Figure 4).7 In other words, surprise billing is the result of a market failure—prices for these services do not reflect competitive market forces. This market failure has driven and been exacerbated by an influx of for-profit physician staffing groups that are backed by private equity.8

FIGURE 4: Ratio of Physician Rates to Medicare Rates

|

Consumers face two negative consequences when their medical providers charge especially high rates. First, when such providers are out-of-network, consumers face high out-of-pocket costs. Second, even if these providers contract to be part of a network, if the contracted rates are high, they will translate to higher premiums.

- Potential surprise billing rates vary by state.9 In 2017, only 3% of emergency department visits in Minnesota had a least one out-of-network charge, compared to 38% of emergency department visits in Texas. Similarly, 2% of in-network admissions in Minnesota resulted in at least one out-of-network charge, compared to 33% in New York. Figure 5 shows the distribution of states by their share of in-network facility visits that included at least one out-of-network charge.

FIGURE 5: Distribution of States by Share of In-Network Hospital Visits With Out-of-Network Charges, 2017

Source: Karen Pollitz, et al., An Examination of Surprise Medical Bills and Proposals to Protect Consumers From Them, Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker, June 20, 2019 (accessed August 26, 2019). |

- Provider payment rates also vary by state.10 Provider payment rates under employer-sponsored insurance plans can vary considerably by state for the same service. For instance, the median payment rate in 2017 for anesthesia for procedures on the lower abdomen (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] code 840) ranged from $458 in Mississippi (where the average allowed Medicare rate was $173) to $1,448 in New Jersey (where the average allowed Medicare rate was $268).

- Several states are taking action to address surprise bills, but federal action is needed to more fully address the problem.11 As of July 2019, 13 states had laws that provide comprehensive protection against surprise bills. These protections hold consumers in both health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and preferred provider organizations (PPOs) harmless by applying in-network cost-sharing requirements and prohibiting balance billing for care received in an emergency department or in-network hospital, and have a payment standard or dispute resolution process for determining how much the provider is paid by the insurer. An additional 15 states have implemented a more limited approach to addressing surprise bills. The 22 remaining states as well as the District of Columbia offer consumers no protections against surprise bills. Even in states with comprehensive protections, however, many consumers remain unprotected. In particular, although states can regulate fully insured plans, they cannot regulate self-funded plans or air ambulances, both of which fall under federal oversight.

Approaches to Address Surprise Billing

Goals of proposals to address surprise-billing problems include reducing out-of-pocket costs and eliminating balance billing for surprise bills and addressing the market failure that has led to such bills. At the same time, proposals aim to retain patient access to needed medical care while also avoiding or limiting any related increases in health insurance premiums.

Most current proposals would base patient out-of-pocket costs on in-network cost-sharing requirements and would prohibit balance billing by providers. This approach would eliminate the surprise billing problem for patients inadvertently receiving out-of-network care. However, it would be only part of any solution to surprise billing. Proposals also need to determine what providers would be paid by insurers. If insurers simply pay out-of-network providers their full charge less any patient cost-sharing, then premiums would increase to reflect the higher out-of-network charges. In addition, paying full out-of-network charges would increase the incentives for providers to be out of network, exacerbating the market failure that helped lead to the surprise billing problem in the first place. On the other hand, if balance billing is banned and there is no payment standard, then providers would have to accept whatever insurers decide to pay, which could lower premiums.

Two primary approaches for paying providers have emerged. One would base insurer payments to applicable out-of-network providers on a benchmark rate, such as the median in-network provider rate. The other would create an independent dispute resolution process, also known as arbitration.

Basing insurer payments on a benchmark rate

Under this approach, insurer payments to applicable out-of-network providers would be based on a benchmark rate, such as the median in-network provider rate or some multiple of Medicare rates. The benchmark would vary by the particular health procedure code and applicable modifiers. In addition, an area-specific benchmark would automatically incorporate any urban-rural or other area-related provider rate differences.

Using a payment benchmark would help mitigate effects of the market failure that arises because patients can’t shop for emergency room and ancillary providers. It could increase the incentives for out-of-network providers to participate on an in-network basis, but potentially at higher payment rates, thereby pushing up median in-network rates. Alternatively, if the benchmark rate is deemed sufficient by out-of-network providers, those providers could simply remain out-of-network.

If benchmark rates are determined using each insurer’s own median in-network rate, alternatives would be needed if an insurer has no in-network providers of a particular specialty in a geographic area.12 In these instances, an area-wide median in-network rate could be used.13 If no insurers in an area have an in-network provider of that specialty, however, another benchmark would be needed, such as the Medicare rate or some multiple thereof. Notably, tying the benchmark to Medicare rates would mitigate the potential for newly in-network providers to push up the in-network median benchmark.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that using the median in-network rate as the payment benchmark would lower insurance premiums, primarily because in-network rates would move toward the median rate, which is lower than the average payment rate.14 In other words, insurers could use the median rate as leverage when contracting with in-network providers that are currently above the median. Using a median in-network payment benchmark could help address the market failure related to the difficulty insurers and large group plans have when negotiating with ancillary providers. Current medical loss ratio (MLR) requirements would help ensure that insurers pass along to consumers any cost savings resulting from lower provider rates in the form of lower premiums.

The higher the benchmark rate, the lower the premium savings; premiums could even increase if the benchmark rate exceeds the current average payment rate. Setting a benchmark based on provider charges could be particularly prone to increasing provider payments and increasing the incentives for providers to be out-of-network. In addition, if patient out-of-pocket costs are based on the benchmark (e.g., through coinsurance requirements), higher benchmarks would result in higher out-of-pocket costs, relative to lower benchmarks. Linking coinsurance to an in-network payment rate regardless of whether a higher benchmark is used would avoid this situation.

Basing provider payments on arbitration

Under this approach, a dispute resolution process would be used to determine payment for out-of-network providers either instead of a payment benchmark or in addition to using a payment benchmark (i.e., a hybrid approach). For instance, with a “baseball-style” arbitration approach, insurers and providers would each submit a payment offer and a neutral arbiter would choose between those offers. Arbitration could be used at the request of the patient, insurer, or provider, or could be triggered automatically for out-of-network bills exceeding a threshold amount. Under a hybrid approach, a benchmark payment rate would be used as the default, but arbitration would be triggered, either upon request or automatically, for claims exceeding a threshold amount.

An arbitration process could put downward pressure on provider payment rates (and premiums) to the extent that providers lower their charges to avoid arbitration and arbiter decisions favor rates lower than average payment rates. However, the arbitration process risks putting upward pressure on provider charges, which could increase both premiums and out-of-pocket costs. For instance, providers could increase their charges to put them in a better bargaining position during arbitration. In addition, arbitration would not address the market failure that contributes to surprise bills.

If arbitration were used, the process would need to be structured carefully to avoid unintended consequences. Such guardrails could include:

- Consideration of a payment benchmark as the default rate. Allowing or requiring the arbiter to consider a relatively low default rate would help put downward pressure on provider payment rates. In addition, if the arbiter could ultimately choose a payment rate lower than the default, providers may limit their requests for arbitration, which would reduce administrative burdens.

- Incorporation of a reasonable range for the payment offers. A floor for insurer offers would help maintain access to providers, and a cap for provider offers would help guard against increasing premiums.

- Transparency. A transparent process that provides information on each party’s offers and the arbiter’s decisions, either individually or in the aggregate, could help provide incentives for both insurers and providers to submit reasonable offers.

- Allocation of arbitration costs. The arbitration process can be administratively burdensome and costly, and those administrative costs could flow through to higher premiums. Requiring the entity that loses in arbitration to pay the costs provides incentives for the parties to submit reasonable payment offers and avoid unnecessary disputes. Alternatively, the costs could be shared by both parties, which could provide an incentive to reach a pre-arbitration settlement.

- Reasonably high thresholds. Under a hybrid approach, any thresholds used to trigger arbitration rather than a payment benchmark should be high enough to limit the cases that go to arbitration. This would minimize the administrative burdens and reserve arbitration for the most costly cases.

Conclusion

Surprise bills occur when patients inadvertently receive care from an out-of-network provider. These bills can occur more frequently in situations when patients have little or no choice over a physician, such as in an emergency room or for ancillary services associated with an inpatient admission. Physicians can charge more for these services because they don’t need to negotiate lower rates or join a network to guarantee patient volume. Although many states have implemented comprehensive laws to address surprise bills, most haven’t. And even those that have such laws leave individuals covered by self-funded employer plans unprotected, because those plans are exempt from state law.

Federal action could result in more comprehensive protections for consumers. Most proposals would base out-of-pocket costs for surprise bills on in-network cost-sharing requirements. Proposals differ, however, regarding what insurers would pay out-of-network providers. One approach would base insurer payments on a benchmark rate, such as the median in-network provider rate or a multiple of Medicare rates. If set below the average in-network rate, a benchmark rate could lead to lower provider payments and premiums, and could provide increased incentives for out-of-network providers to join a network. A benchmark rate could help mitigate the market failure that results in emergency room and ancillary physicians opting to stay out-of-network with charges much higher than other specialties.

Craig Hanna, Director of Public Policy Cori E. Uccello, Senior Health Fellow Members of the Health Practice Council include: Audrey Halvorson, MAAA, FSA—vice president; Tammy Tomczyk, MAAA, FSA, FCA— vice chairperson; Joseph Allbright, MAAA, ASA; Alfred Bingham, MAAA, FSA; Joyce Bohl, MAAA, ASA; April Choi, MAAA, FSA; Tim Deno, MAAA, FSA; Colleen O’Malley Driscoll, MAAA, FSA, FCA, EA; Barbara Klever, MAAA, FSA; Marc Lambright, MAAA, FSA; Michael Nordstrom, MAAA, ASA; Susan Pantely, MAAA, FSA; Allen Schmitz, MAAA, FSA; John Schubert, MAAA, FCA, ASA; Bruce Stahl, MAAA, ASA; Michael J. Thompson, MAAA, FSA; and Cori E. Uccello, MAAA, FSA, FCA, MPP. Uccello, who is the Academy’s senior health fellow, was the primary drafter of this issue brief. |