End-of-Life Care in an Aging World: A Global Perspective

|

For a print-ready PDF of this page, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

It is critical that the impact of changing demographics on health care systems is understood in the context of complex financial, social, public health, and cultural boundaries. Using examples from Japan, the United States (U.S.), the United Kingdom (U.K.), China, Israel, India, and the Netherlands, this issue brief explores the increased health care costs of global aging, quality of life during the end-of-life-period, palliative versus curative care, and stakeholder strategies for addressing the unique health care challenges at the end of life.

The Aging Population

According to the United Nations (U.N.), the global population will age significantly in the first half of this century. Collectively, the number of people over the age of 65 across the globe will increase by nearly 370 million from 2015 to 2030—more than 60 percent. Additionally, the U.N. predicts the rate of the population aging in the 21st century will exceed that of the previous century, and people age 65 and older will soon outnumber children five and under.3

This demographic shift from 2015-2030 will be felt in nearly all countries, but some will feel it more acutely than others. (See Figure 1.) Japan, which already has one of the highest proportions of people over age 65, will see its elderly population increase from 25 percent to nearly 30 percent of the populace. The Netherlands will see the proportion of its 65 and older population increase from 17 percent to 24 percent. In absolute numbers, China and India will see their population age 65 and over increase by 100 million and 50 million people, respectively.4

This remarkable shift in demographics and increase in longevity is the result of several factors. First, significant improvements in public health and a widespread decrease in communicable diseases have been experienced. Second, the advancements in medical treatments and technology have extended the length of life, the result of which has contributed to an increased share of elderly in the population. Third, fertility has declined, resulting in fertility levels below the population replacement rate of 2.1 live births per woman. (See Figure 1.)

These demographic changes strain health care systems as fewer working-age adults support an increasingly older population. (See Figure 2.) The rate of this shift varies by country, but the faster the shift, the less time a society has to prepare for the change. Additionally, the impact of and the actions required to address the strain may vary by the type of health care systems within each country.

The Cost of End-of-Life Care

So, instead of focusing on intensive procedures with little clinical benefit that do not improve the quality of life, some research is now focusing on the “quality of death.” This research compares quality of palliative care in 80 countries. Income level was found to be a driver for quality of care, however lower-income countries showed innovation through the growth of palliative care teaching programs.

Quality of Death

The index uses 24 indicators, which fall into three categories:

The scores from each indicator were aggregated and normalized for comparison. The U.K., Australia, and New Zealand top the overall ranking. Their high scores are attributed to the relative wealth, advanced infrastructure, and established end-of-life care initiatives. The bottom of the overall ranking includes developing countries: Mexico, China, Brazil, Uganda, and India. (See Figure 4.) Developing countries generally lack money and recognition in government policy for end-of-life care, resulting in little palliative care development.

Curative vs. Palliative Care

This demographic shift from 2015-2030 will be felt in nearly all countries, but some will feel it more acutely than others. (See Figure 1.) Japan, which already has one of the highest proportions of people over age 65, will see its elderly population increase from 25 percent to nearly 30 percent of the populace. The Netherlands will see the proportion of its 65 and older population increase from 17 percent to 24 percent. In absolute numbers, China and India will see their population age 65 and over increase by 100 million and 50 million people, respectively.4

|

This remarkable shift in demographics and increase in longevity is the result of several factors. First, significant improvements in public health and a widespread decrease in communicable diseases have been experienced. Second, the advancements in medical treatments and technology have extended the length of life, the result of which has contributed to an increased share of elderly in the population. Third, fertility has declined, resulting in fertility levels below the population replacement rate of 2.1 live births per woman. (See Figure 1.)

|

The Cost of End-of-Life Care

The increasing incidence of non-communicable conditions—such as Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, dementia, and heart disease—means the nature of care must also shift. In the past, societies had to let these conditions take their course. Due to advances in medicine and technology reinforced by the traditional “first do no harm” medical approach, health care practitioners can now take extraordinary measures to sustain life and forestall death—with a dramatic impact on costs during the last years of life. A 2011 study in the United States indicated that claims follow a U-shaped distribution, with the highest costs in the initial phase after diagnosis and in the year prior to death, and a decline in the in-between phase. (See Figure 3.)5 Pancreatic cancer in males 65 or over, for example, incurred over $90,000 in the phase just after diagnosis, decreased to roughly $10,000 in the “in-between” phase, and increased to over $110,000 in the phase just before death.6

This kind of spending pattern results in annual costs per deceased elderly that were found to be more than six times higher than that of surviving elderly in the U.S.7 Similarly in Japan, health care expenditures per deceased elderly for the one year prior to death were 4.3 times higher than annual health care expenditure per surviving elderly.8

The costs of extraordinary efforts to sustain life for very ill patients can place significant financial strain on societies and families. In China, for example, the cost of cancer care in the last three months of life was about $17,000 in 2012 U.S. dollars, which far exceeded the income available to most households.9

Aggressive treatments at the end of life have been increasing with little signs of abating.10 The focus of this care is to extend and improve the quality of life. However, these outcomes may or may not be possible given the conditions facing the elderly. Studies indicate that the use of multiple and intensive services at the end of the life has little clinical benefit and may bring unnecessary pain.11 A 2009 study by the Social Security Advisory Board suggests that the U.S. government could achieve significant health care savings and reduce unnecessary services by focusing on quality of care instead of quantity and changing provider payment agreements to reimburse for value of care.12

|

This kind of spending pattern results in annual costs per deceased elderly that were found to be more than six times higher than that of surviving elderly in the U.S.7 Similarly in Japan, health care expenditures per deceased elderly for the one year prior to death were 4.3 times higher than annual health care expenditure per surviving elderly.8

The costs of extraordinary efforts to sustain life for very ill patients can place significant financial strain on societies and families. In China, for example, the cost of cancer care in the last three months of life was about $17,000 in 2012 U.S. dollars, which far exceeded the income available to most households.9

So, instead of focusing on intensive procedures with little clinical benefit that do not improve the quality of life, some research is now focusing on the “quality of death.” This research compares quality of palliative care in 80 countries. Income level was found to be a driver for quality of care, however lower-income countries showed innovation through the growth of palliative care teaching programs.

Quality of Death

The end-of-life period is not just the last year or short period before death. With medical advancements, many people today are living with terminal illness for a long period (e.g., cases of dementia and advanced heart disease). Thus, the end of life is considered to be the period when there is no recovery or cure and, as health degrades, the only end is death. In essence, it is a process of prolonged death. Beyond that, end of life is characterized by degradation in the quality of life, or—more accurately—by the quality of the prolonged death.

Traditional health care systems are curative-oriented and tend to keep patients alive—even at the cost of pain, suffering, and reduction in their quality of life, regardless of the expected success of the care. The preparation or planning for death remains outside the process of normal care, leaving those who are living with terminal illness with limited access or opportunity to choose their preferred level of medical intervention.

To respond to these issues, various initiatives around the world have started focusing health care providers, local communities, and family caregivers on improving the quality of death. However, according to the Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance, “42% of the world has no hospice and palliative care services and in an additional 32% of countries, palliative care services reached only a small percentage of the population. Palliative care is integrated in only 8.5% of country health systems; therefore 91.5% of health systems globally do not yet have integrated palliative care.”13

To bring the “quality of death” issues to light, the Lien Foundation commissioned the Economist Intelligence Unit to develop a “Quality of Death Index.”14 This index measures the current environment for end-of-life care services in 40 countries.

The index scores countries in four categories:

Traditional health care systems are curative-oriented and tend to keep patients alive—even at the cost of pain, suffering, and reduction in their quality of life, regardless of the expected success of the care. The preparation or planning for death remains outside the process of normal care, leaving those who are living with terminal illness with limited access or opportunity to choose their preferred level of medical intervention.

To respond to these issues, various initiatives around the world have started focusing health care providers, local communities, and family caregivers on improving the quality of death. However, according to the Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance, “42% of the world has no hospice and palliative care services and in an additional 32% of countries, palliative care services reached only a small percentage of the population. Palliative care is integrated in only 8.5% of country health systems; therefore 91.5% of health systems globally do not yet have integrated palliative care.”13

To bring the “quality of death” issues to light, the Lien Foundation commissioned the Economist Intelligence Unit to develop a “Quality of Death Index.”14 This index measures the current environment for end-of-life care services in 40 countries.

The index scores countries in four categories:

- Basic end-of-life health care environment

- Availability of end-of-life care

- Cost of end-of-life care

- Quality of end-of-life care

The index uses 24 indicators, which fall into three categories:

- Quantitative indicators—e.g., life expectancy, health care spending as a percentage of GDP

- Qualitative indicators—assessments of end-of-life care in individual countries (e.g., public awareness of end-of-life care)

- Status indicators—whether something is or is not the case (e.g., existence of a government-led national palliative care strategy)

The scores from each indicator were aggregated and normalized for comparison. The U.K., Australia, and New Zealand top the overall ranking. Their high scores are attributed to the relative wealth, advanced infrastructure, and established end-of-life care initiatives. The bottom of the overall ranking includes developing countries: Mexico, China, Brazil, Uganda, and India. (See Figure 4.) Developing countries generally lack money and recognition in government policy for end-of-life care, resulting in little palliative care development.

|

As stated above, curative care is intended to improve the quality of life and extend life. However, as chronic diseases progress in the elderly and life nears its end, curative care may no longer yield the desired improvement in quality of life, so palliative care, often followed by a hospice stay, becomes an option. (See Figure 5.)

Palliative care is an effective alternative to continued curative care. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as:

Curative care using extensive measures to continue life—even when this care provides little benefit and can conflict with the desires of the patient—is often used today. There are several reasons for this. First, families in all societies cherish life and want to continue care for fear of “giving up.” Second, physicians are primarily trained in curative care as opposed to palliative care. Third, most physicians receive minimal training in discussing the transition to other forms of care that may be more appropriate at the end of life. Finally, public policy and health care systems are traditionally not designed to consider the inclusion of palliative care.

Palliative care is an approach that:

Potential Strategies for Stakeholders

Public Policy

While most countries with extensive social welfare programs fund their public programs on a pay-as-you-go basis, few countries have fully funded systems. But governments have several levers that can be pulled to address the changing demographics of aging populations.

An audit of the program after a 22-month period showed that of the 57 patients who died, 91 percent were able to die in the place of their choice, 67 percent were able to stay in their own place of residence (versus 35 percent for the national average), and only 12 percent died in the hospital (compared with the national average of 58 percent).

Providers

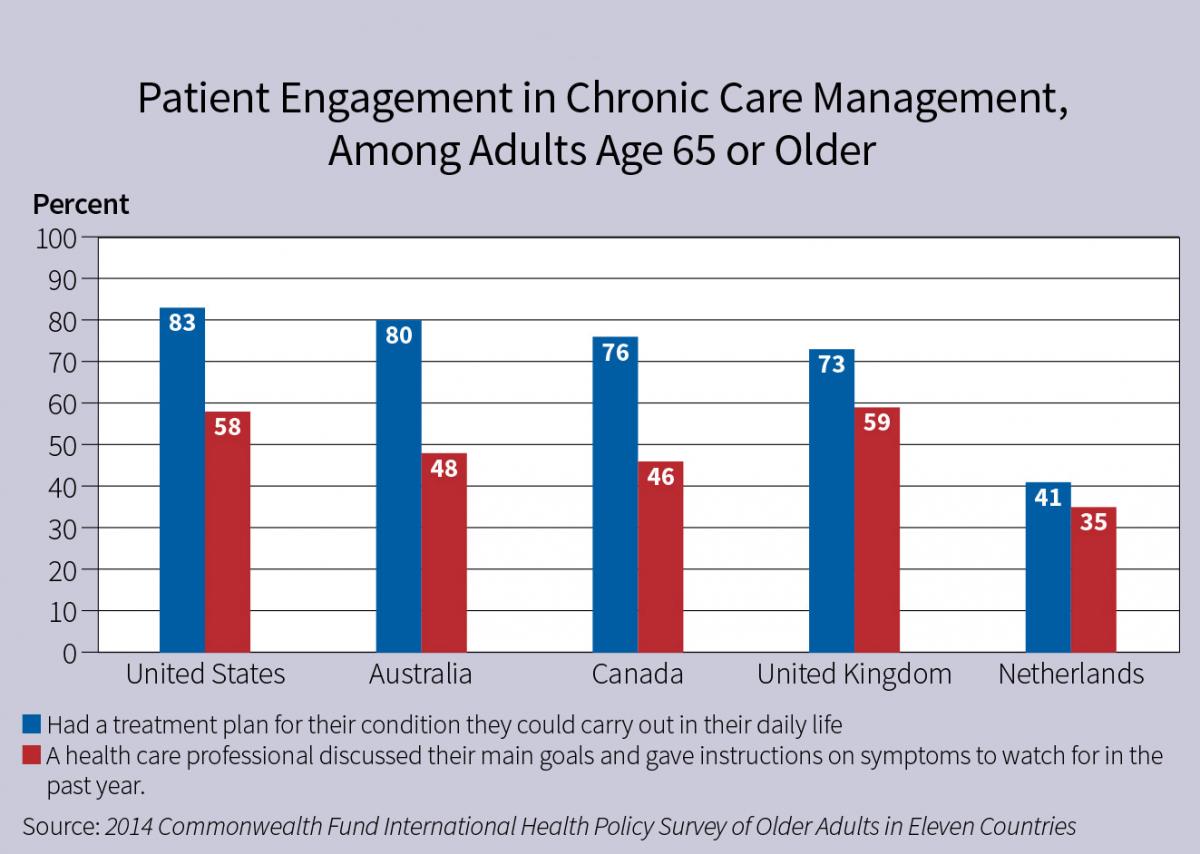

Aging is often associated with the decline in physical or mental capacity. Many elderly will develop life-threatening illnesses in which the progression of the illness inevitably leads to death. This progression should be matched by the nature of the care provided and the wishes and desires of the elderly patient and their family. Therefore, patient engagement is necessary.

This engagement is already taking place in several countries. (See Figure 6.) Unfortunately, there are still gaps. For example, cultural norms in China are such that doctors rely on families to make crucial health care choices, rather than patients.21

Support and caregiving have historically flowed in both directions among generations. While the aging population may increase the number of surviving generations, the global trend toward fewer children means fewer family members to provide care to the elderly. Exacerbating this is the trend toward generations living separately. For example, in Japan the percentage of people over age 65 living with children decreased from 87 percent in 1960 to 47 percent in 2005.22

This demographic shift has not changed a family’s desire to provide as much care as possible. Indeed, there appears to be a concern that they are “giving up” if they don’t do everything possible to provide such care. In Japan, for example, additional payments for providing information on end-of-life care to elderly terminally ill patients and their families, and making a written agreement on such care, were terminated due to strong opposition by the elderly and the media.23 In the United States, a provision that would have paid physicians for providing voluntary counseling to Medicare patients about living wills, advance directives, and end-of-life care options was struck from the final legislation that became the Affordable Care Act due to the public’s concern and the debate over “death panels.”

Families around the world are acting as surrogates for the elderly in making health care decisions. However, discussions about what to do if elderly patients become unable to make their own decisions vary by country. Interestingly, even though these discussions have taken place, few elderly have a written plan naming someone who will make treatment decisions if they are unable to do so, and even fewer have a written plan describing the treatment they want at the end of life. (See Figure 7.)

Families and individuals can take action to alleviate some of these issues. For example, advance directives are documents informing caregivers and families about one’s intentions and preferences should they be unable to make the decisions themselves. These documents serve to improve communication, decrease the guilt and stress families may feel and lower costs by providing only the care the patient desires near the end of life.

The elderly and their families and caregivers also can discuss advanced care planning.24 With a greater understanding of the progression of an elderly patient’s disease, the patient, the family, and their caregivers can make medical decisions based on anticipation of what may happen. The plan might include:

Finally, patients and families can understand the care options available and choose accordingly given the possible outcomes of those options and their personal situations.

Insurance Companies

Given the importance of adequate end-of-life care for patients and the significant financial stake insurance companies have in shouldering the cost, private insurers can be part of the solution in providing funding to accommodate the shift in types of health care needed in the coming years.

Private insurers can expand the traditional insurance coverage to include new types of treatment with respect to end-of-life care. Such insurance offerings could include supplementary coverage, critical illness coverage, and links to disability or life insurance. Combinations may prove to be an effective way of offering alternatives for patients and their families.

Finally, insurance companies can expand their role to be more involved in piloting end-of-life care by working with health care financing and health care systems. These private initiatives can be used in conjunction with public initiatives that may take place.

Looking Ahead

|

Palliative care is an effective alternative to continued curative care. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as:

The active total care of patients whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment. Control of pain, of other symptoms, and of psychological, social and spiritual problems, is paramount. The goal of palliative care is achievement of the best quality of life for patients and their families.15

Curative care using extensive measures to continue life—even when this care provides little benefit and can conflict with the desires of the patient—is often used today. There are several reasons for this. First, families in all societies cherish life and want to continue care for fear of “giving up.” Second, physicians are primarily trained in curative care as opposed to palliative care. Third, most physicians receive minimal training in discussing the transition to other forms of care that may be more appropriate at the end of life. Finally, public policy and health care systems are traditionally not designed to consider the inclusion of palliative care.

Palliative care is an approach that:

- Does not hasten or postpone death;

- Provides relief from pain and other symptoms;

- Offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible right up to their death;

- Integrates psychological and spiritual care; and

- Provides a wider support to help the family cope during both the patient’s illness and their own bereavement after death.16

Potential Strategies for Stakeholders

Public Policy

While most countries with extensive social welfare programs fund their public programs on a pay-as-you-go basis, few countries have fully funded systems. But governments have several levers that can be pulled to address the changing demographics of aging populations.

One such lever is financing, and governments could address solvency concerns and ensure programs are sustainable into the future. Possible approaches include increasing taxes or adjusted enrollee contributions (e.g., varying contributions by income). While these approaches are not politically easy or palatable, they may be necessary.

Laws and regulations could also be used to improve the efficiency of health care systems and direct resources to the most appropriate and effective responses. For example, current reimbursement methodologies can create incentives for interventions that don’t improve outcomes or the quality of life, and that may not align with the needs of the population. These methodologies could be changed to improve incentives, align patient and provider desired services, and improve quality. Japan, for instance, has issued guidelines for home-care support clinics and introduced fee schedules for clinics registered for provider-planned home care.17

Contribution and eligibility requirements could also be used to better align an aging population to the available social welfare programs. The simplest example would be to adjust contributions by income, depending on a nation’s health care system. Additionally, eligibility for certain benefits could be changed. Criteria used to determine hospice eligibility could be changed to make this benefit a more effective option for end-of-life care.

Integration of the various forms and levels of health care can improve service and the quality of life of patients while saving costs. Israel, for example, has a National Health Act that provides health care from conception to death—including palliative care—for all residents. It is integrated with wide-ranging public community services, long-term care coverage available to about 70 percent of the population, and—notably—many volunteer community groups and services.

Finally, benefits could be adjusted by aligning covered services and cost sharing to incentivize the utilization of services. For example, in China, palliative care is not provided or reimbursed through its health care system,18 and patients and their families must pay fully out of pocket for the care. Adjustments could be made, however, to meet the needs of the covered populations.

Communities

Local communities also might assist in improving care for the elderly at the end of life. Approaches will vary based on demographics, income levels of the community, and the availability of health care.

One good example of how a community is coping with these issues is Kerala, India. Although India as a country ranks at the bottom on the “quality of death” index, there is a community-based, end-of-life care system in Kerala that has served as a model for many other communities across the globe. This model is based on the principles that the community should be empowered to take ownership of end-of-life care, and that services should be made accessible to individuals and families at a cost that is sustainable for the community.19

The Kerala model is built upon a neighborhood network of volunteers who have been trained to identify patients who are chronically ill and are near the end of their lives. The volunteers are connected with outpatient-based, local palliative-care centers that provide support from trained palliative-care nurses and physicians. Volunteers supplement the health care professionals with psychological, social, and spiritual support that is culturally and socioeconomically appropriate to the patients and their families.

Since its start in 2000, the network has expanded to 50 palliative care physicians, 100 palliative care nurses, and 15,000 trained community volunteers. Having seen the value this model has brought to the community, the local government in Kerala has started contributing funds to support the network. Although Kerala has only 3 percent of India’s population, the network is providing two-thirds of India’s end-of-life services.

Laws and regulations could also be used to improve the efficiency of health care systems and direct resources to the most appropriate and effective responses. For example, current reimbursement methodologies can create incentives for interventions that don’t improve outcomes or the quality of life, and that may not align with the needs of the population. These methodologies could be changed to improve incentives, align patient and provider desired services, and improve quality. Japan, for instance, has issued guidelines for home-care support clinics and introduced fee schedules for clinics registered for provider-planned home care.17

Contribution and eligibility requirements could also be used to better align an aging population to the available social welfare programs. The simplest example would be to adjust contributions by income, depending on a nation’s health care system. Additionally, eligibility for certain benefits could be changed. Criteria used to determine hospice eligibility could be changed to make this benefit a more effective option for end-of-life care.

Integration of the various forms and levels of health care can improve service and the quality of life of patients while saving costs. Israel, for example, has a National Health Act that provides health care from conception to death—including palliative care—for all residents. It is integrated with wide-ranging public community services, long-term care coverage available to about 70 percent of the population, and—notably—many volunteer community groups and services.

Finally, benefits could be adjusted by aligning covered services and cost sharing to incentivize the utilization of services. For example, in China, palliative care is not provided or reimbursed through its health care system,18 and patients and their families must pay fully out of pocket for the care. Adjustments could be made, however, to meet the needs of the covered populations.

Communities

Local communities also might assist in improving care for the elderly at the end of life. Approaches will vary based on demographics, income levels of the community, and the availability of health care.

One good example of how a community is coping with these issues is Kerala, India. Although India as a country ranks at the bottom on the “quality of death” index, there is a community-based, end-of-life care system in Kerala that has served as a model for many other communities across the globe. This model is based on the principles that the community should be empowered to take ownership of end-of-life care, and that services should be made accessible to individuals and families at a cost that is sustainable for the community.19

The Kerala model is built upon a neighborhood network of volunteers who have been trained to identify patients who are chronically ill and are near the end of their lives. The volunteers are connected with outpatient-based, local palliative-care centers that provide support from trained palliative-care nurses and physicians. Volunteers supplement the health care professionals with psychological, social, and spiritual support that is culturally and socioeconomically appropriate to the patients and their families.

Since its start in 2000, the network has expanded to 50 palliative care physicians, 100 palliative care nurses, and 15,000 trained community volunteers. Having seen the value this model has brought to the community, the local government in Kerala has started contributing funds to support the network. Although Kerala has only 3 percent of India’s population, the network is providing two-thirds of India’s end-of-life services.

Another example of a community-based approach is England’s Community Nurse Development Programme, which emphasizes the importance of district nurses and the integration of health care services provided to local populations. In Cambridge, England, a team of caregivers questioned and then changed how they worked together and integrated their care in order to better meet the wishes of people in their end-of-life care.20

Changes in the caregivers’ practices included:

Changes in the caregivers’ practices included:

- Establishing regular meetings about once every other month;

- Developing a patient list to include anyone believed to be in the last year of life with any underlying disease;

- Proactively discussing preferred priorities for care with patients and their families;

- Requiring care givers to write patient information in the same electronic notes; and

- Routinely updating out-of-hours services with patient information.

An audit of the program after a 22-month period showed that of the 57 patients who died, 91 percent were able to die in the place of their choice, 67 percent were able to stay in their own place of residence (versus 35 percent for the national average), and only 12 percent died in the hospital (compared with the national average of 58 percent).

Providers

Aging is often associated with the decline in physical or mental capacity. Many elderly will develop life-threatening illnesses in which the progression of the illness inevitably leads to death. This progression should be matched by the nature of the care provided and the wishes and desires of the elderly patient and their family. Therefore, patient engagement is necessary.

This engagement is already taking place in several countries. (See Figure 6.) Unfortunately, there are still gaps. For example, cultural norms in China are such that doctors rely on families to make crucial health care choices, rather than patients.21

|

Increasing the training of health care providers in the needs of the elderly with chronic conditions who are near the end of life can help align the progression of the illness with the desires of the patient and the end-of-life care plan. The health system can also encourage increases in trained palliative care providers.

Families and IndividualsSupport and caregiving have historically flowed in both directions among generations. While the aging population may increase the number of surviving generations, the global trend toward fewer children means fewer family members to provide care to the elderly. Exacerbating this is the trend toward generations living separately. For example, in Japan the percentage of people over age 65 living with children decreased from 87 percent in 1960 to 47 percent in 2005.22

This demographic shift has not changed a family’s desire to provide as much care as possible. Indeed, there appears to be a concern that they are “giving up” if they don’t do everything possible to provide such care. In Japan, for example, additional payments for providing information on end-of-life care to elderly terminally ill patients and their families, and making a written agreement on such care, were terminated due to strong opposition by the elderly and the media.23 In the United States, a provision that would have paid physicians for providing voluntary counseling to Medicare patients about living wills, advance directives, and end-of-life care options was struck from the final legislation that became the Affordable Care Act due to the public’s concern and the debate over “death panels.”

Families around the world are acting as surrogates for the elderly in making health care decisions. However, discussions about what to do if elderly patients become unable to make their own decisions vary by country. Interestingly, even though these discussions have taken place, few elderly have a written plan naming someone who will make treatment decisions if they are unable to do so, and even fewer have a written plan describing the treatment they want at the end of life. (See Figure 7.)

|

Families and individuals can take action to alleviate some of these issues. For example, advance directives are documents informing caregivers and families about one’s intentions and preferences should they be unable to make the decisions themselves. These documents serve to improve communication, decrease the guilt and stress families may feel and lower costs by providing only the care the patient desires near the end of life.

The elderly and their families and caregivers also can discuss advanced care planning.24 With a greater understanding of the progression of an elderly patient’s disease, the patient, the family, and their caregivers can make medical decisions based on anticipation of what may happen. The plan might include:

- A selection of a well-informed and trusted person to make health care decisions for the patient if the patient is unable to do so;

- The creation of instructions based on a patient’s health condition and preferences; and

- Teaming between physicians and other caregivers to incorporate these care options with other medical decisions.

Finally, patients and families can understand the care options available and choose accordingly given the possible outcomes of those options and their personal situations.

Insurance Companies

Given the importance of adequate end-of-life care for patients and the significant financial stake insurance companies have in shouldering the cost, private insurers can be part of the solution in providing funding to accommodate the shift in types of health care needed in the coming years.

Private insurers can expand the traditional insurance coverage to include new types of treatment with respect to end-of-life care. Such insurance offerings could include supplementary coverage, critical illness coverage, and links to disability or life insurance. Combinations may prove to be an effective way of offering alternatives for patients and their families.

Finally, insurance companies can expand their role to be more involved in piloting end-of-life care by working with health care financing and health care systems. These private initiatives can be used in conjunction with public initiatives that may take place.

Looking Ahead

The issues surrounding end-of-life care for the elderly will become more severe due to the aging population and shifting demographics. However, very few countries have begun the long-term planning required to meet the ongoing challenges. As the pace of the population aging accelerates and a greater portion of countries’ gross domestic product is consumed by health care and other social programs for the elderly, the solutions will become increasingly difficult to implement and place significant economic burdens on this generation and the next.

Solutions for the increasing burden of health care costs and care of the elderly at the end of life are multifaceted and should consider public policy, financial constraints, regional differences, personal considerations, as well as individual and family positions. They must also be supported by all stakeholders—the elderly, families, providers, and policymakers.

Policymakers can redirect national, regional, and local resources as well as set policies to assist in aligning the incentives. Provider solutions can include realistically assessing the clinical effectiveness of end-of-life care, the additional training for palliative care, and contracts that align incentives for end-of-life care. Individuals and families can also be realistic about the outcome of the care they discuss with their providers, learn more about the progression of chronic diseases they or their family member may suffer from, and put into place advance directives and care plans.

While none of these solutions will be easy, holistic considerations of the elements of end-of-life care are necessary to effectively address the shifting needs of the elderly population.

Solutions for the increasing burden of health care costs and care of the elderly at the end of life are multifaceted and should consider public policy, financial constraints, regional differences, personal considerations, as well as individual and family positions. They must also be supported by all stakeholders—the elderly, families, providers, and policymakers.

Policymakers can redirect national, regional, and local resources as well as set policies to assist in aligning the incentives. Provider solutions can include realistically assessing the clinical effectiveness of end-of-life care, the additional training for palliative care, and contracts that align incentives for end-of-life care. Individuals and families can also be realistic about the outcome of the care they discuss with their providers, learn more about the progression of chronic diseases they or their family member may suffer from, and put into place advance directives and care plans.

While none of these solutions will be easy, holistic considerations of the elements of end-of-life care are necessary to effectively address the shifting needs of the elderly population.

| 1. | United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision,” 2013. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 2. | National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, “Why Population Aging Matters—A Global Perspective,” March 2007. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 3. | United Nations, op. cit. |

| 4. | Ibid. |

| 5. | Angela B. Mariotto, K. Robin Yabroff, Yongwu Shao, Eric J. Feuer, Martin L. Brown, “Projections of the Cost of Cancer Care in the United States: 2010–2020,” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Jan. 19, 2011. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 6. | Ibid. |

| 7. | James Lubitz and Gerald Riley. “Long-Term Trends in Medicare Payments in the Last Year of Life,” Health Services Research, Feb. 9, 2010. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 8. | International Longevity Center – Japan, “End-of-life Care: Japan and the World,” March 2011. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 9. | Paul Gross, et al., “Challenges to effective cancer control in China, India, and Russia,” Lancet Oncology Commission, April 2014. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 10. | Darius Lakdawalla, Anupam B. Jena, Dana Goldman, David B. Agus, “Medicare end-of-life counseling: a matter of choice,” American Enterprise Institute, Aug. 15, 2011. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 11. | The Medicare NewsGroup, “The Cost and Quality Conundrum of American End-of-Life Care,” June 5, 2013. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 12. | Social Security Advisory Board, “The Unsustainable Cost of Health Care,” September 2009. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 13. | Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance, “Palliative Care and the Global Goal for Health,” Dec. 2015. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 14. | Economist Intelligence Unit, “The Quality of Death: Ranking end-of-life care across the world,” 2010. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 15. | National Council for Palliative Care, “Palliative Care Explained,” undated. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 16. | J. Stjernswärd, et al., “The public health strategy for palliative care,” Journal of Pain Symptom Management, 2007. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 17. | Taro Tomizuka and Ryozo Matsuda, “Promoting end-of-life care outside hospitals,” Health Policy Monitor, October 2008. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 18. | Xi Zhang, “Palliative Care for the Ageing Group in China,” International Forum on Ageing in Place and Age Friendly Cities, undated. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 19. | Economist Intelligence Unit, op. cit. |

| 20. | Department of Health, “Care in local communities—a new vision and model for district nursing,” January 2013. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 21. | Gross, op. cit. |

| 22. | Japan National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, “Population Statistics of Japan,” 2008. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

| 23. | Tomizuka, op. cit. |

| 24. | AHA Committee on Performance Improvement, “Advanced Illness Management Strategies,” August 2012. (Accessed Nov. 17, 2017.) |

Share